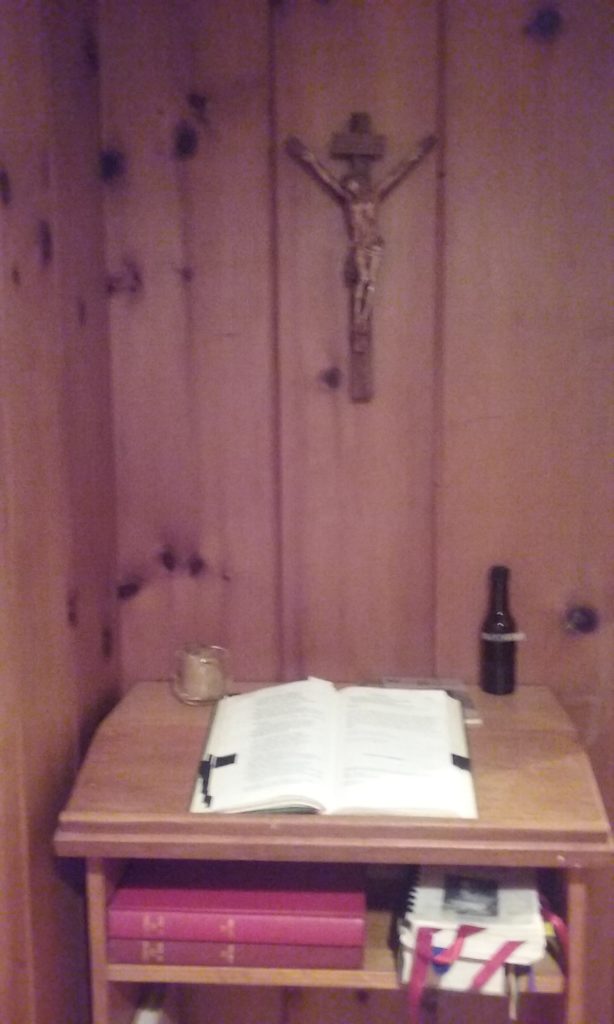

The Carthusian life fits nicely. The austere nature perceived exist, yet within there is an ease I did not anticipate. There is a binder provided in the cell that outlines Carthusian life for a retreatant spending time at the monastery. Words guiding a retreatant toward prayer in one’s cell demonstrates the nature of the ease with which an austere life of solitude and silence is presented. In fact, a simple rule for you when you’re in Church would be to simply follow the monks’ postures. When you’re in your cell, and to simplify matters for you, you may either kneel, stand, or incline on the mesirecord as your piety dictates. Later on, when you become a postulant, God willing, the proper postures will be taught to you. Meanwhile, do what you can with calmness, peace, and recollection. If your counting, that is three times a form of the word simple is used. The novice master, an oriental priest, embodies the humble unpretentious manner employed toward a cloistered life centering upon prayer, solitude, and silence, obedient within the body of the Church. His friendly disposition, emanating from a peaceful joyful personality, is unassuming in conversation. Father is open, interested, and interesting. He came alive when telling me the history of the Carthusian monastery in Vermont, embolden by a funny story involving the founder’s wife. The founder was a doctor, although Father also spoke of him as a chemical engineer receiving important patens involving the nylon industry, as well as an important figure in designing atomic bombs. He was a well-connected man with the United States department of defense. A New Yorker, also living in California for a period, the founder decided to seek out large portions of land to purchase. He settled upon a mountain in Vermont, the mountain he would leave to the Carthusian order, after passing away with no children. Upon my arrival, I was led up the mountain by a man, a visitor to the monastery from Toronto, brother to the procurator. The man led me to a mountain top mansion, strange in regard that the expensive furniture dated itself from the fifties or sixties. The empty mansion was immaculate in cleanliness and good taste, obviously unoccupied for years. In one sitting room, two enormous painted portraits individually displayed the husband and wife lording over the home, beautiful people of charm and distinction from years gone by. I was left alone in the home, wandering out to an extensive wooden patio. The nighttime view from the balcony was stunning. There beneath me was the descent of the mountain, a valley and several rises leading to neighboring mounts. I felt the area was desolate, yet now I saw the lights of hundreds of homes. The surrounding population was much denser than imagined. It was breathtaking. I could only imagine how much the homeowners treasured their precious mountaintop view. Father explained how the founder used military connections to have a hydro damn constructed on the mountain, the monastery currently producing so much electricity it can sell some back to the surrounding community. An interesting side note, a telling of the story of humanity, the founder is considered an invading outsider by much of the community. He was regarded with disdain by many of the locals for coming in and buying out over seven thousand acres of prime property, offering amounts to poorer families who could not refuse his high offers. He ended up owning the entire mountain. Father, the novice master, told the story he found so amusing regarding the founder’s wife. The woman was sitting on her balcony at night, watching over the community, when suddenly the lights for the homes began turning off one at a time, until eventually all the lights for the homes where silent. During the time of the Cold War, the woman feared a Russian airstrike took out the electricity, convincing herself a Russian attack upon the United States had ensued. It was one of the factors leading her husband to build his own massive generator. Of course, there was no Russian attack. Father found the story hilarious. I found his inability to withhold his eruption of laughter hilarious. He also made me laugh when telling me one of the workers, one of the four locals employed by the monastery to look over the property and hydro-damn, was off for the week deer hunting in Maine. He told me how popular deer hunting was for the locals in Vermont. I told him I understood as I stopped at nearby roadside woodcarving facility, an establishment that specialized in huge tree trunk chainsaw wood carvings of bears, deer, raccoons, and other such statues; there I heard a group of local men talking excitedly about deer season while dressed in hunting fatigues. Father explained they determined there would be no hunting on their property since they often went for walks, plus the concern of accidents occurring. He said the monks do not hunt because he does not think it would look right for the monks to be carrying around guns looking to shot animals. His remark was so earnest and straightforward it aroused an internal chuckle and the words, ‘I think I see what you mean’. He told how smart he thinks deer are because the monastery property is densely populated by deer during the hunting season. Driving up the mountain, I remarked I witnessed three groups of deer. Father and I held our conversation in my designated cell, warmed by a fire in the cell’s wood burner. The wood burner has graced my visit with warmth and charm. Centered in the room, the wood burner brings distinction to the Carthusian life. Outside my cell, is a storage area, an entrance hall filled with stacked lumber. The morning of my first waking I was startled to find inches of snow. Winter was upon me and now God graced a wood burning stove. I find it such a pleasure to work the wood burner, placing the fire-starting bark and paper first, then kindling, and finally larger pieces or birch wood. At first, I was overstuffing the wood-burner, creating such immense heat I was forced to open my window and let the cold air in. I have found a delicate balance, placing one piece of lumber at a time, allowing the stove to simmer by utilizing the damper, while also opening the windows when the heat becomes too much. The wood burner reaches temperatures close to four hundred degrees thus overheating is a concern. The rest of the monastery is quite cold, including the Church. Concrete in construction, the walls become frigid—an austere strength and isolation exist within the confines of the monastery. During prayers and Mass, coldness dominates. Sunday midnight prayer, Matins for Monday, commenced for nearly three hours honoring the Presentation of Mary. Profound in experience, it proved also suffering as the cold bore down heavy with the passing of hours. I found myself longing for a return to the warmth of my cell, to the warmth of solitude and my wood-burner. It is close to eight o’clock and time for sleep.