This will be a longer post, coinciding with my decision, guided by my Cuban poet friend, to pursue an academic path focused upon my commitment to my intellectual passions. I think of the Cuban poet’s startled reaction when I used the word ‘passion’. Her immediate response was a warning against the word, stressing the need to discipline our passions, yet it was intentional, uttered with a contemplative concentration in mind. I do feel the call to bring my thoughts and approach to the academic world, moving forward in applying to John Carroll University, a Jesuit Catholic university.

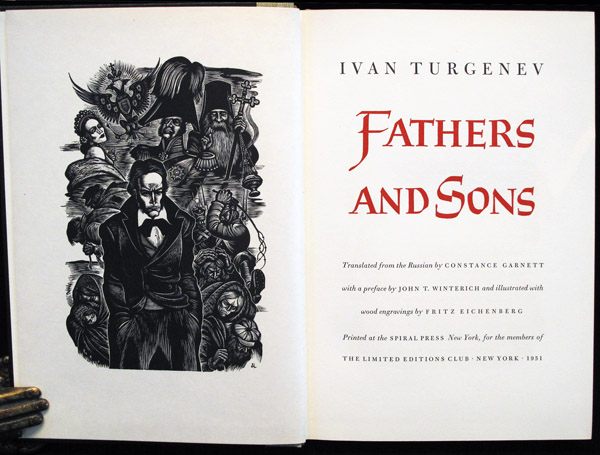

I present this long quote to highlight an insightful novel, Eugene Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’. The novel is often credited for originating the term nihilist; nihilism being the rejection of all authority, the rejection of all religious and moral principles, the acceptance of the fact that life is meaningless. Bazarov, a leading character, a spoiled young man of extreme promise, an impressionable intelligent and intense recent graduate, moves into life, beyond college, as a bold nihilist, one who rejects everything before him. His relationship with his collegemate Arkady creates a major theme within the novel. Turgenev profoundly allows his characters to define one another, their interactions putting forth an implied message of human values and consequences. Going beyond competition, permitting complications to be meditated upon, his characters transform into their fullness of being through their relationships. Life is experiential rather than theoretical. It is not our beliefs and thoughts that establish who we are, rather our experiences and behavior, our willingness to allow life to shape and form us that determines the quality of our life. The fruits of what we think and practice redeems or negates our philosophies. Arkady idolizes Bazarov, convinced his peer possess an intellect and point of view that elevates him above everyone he has ever met. Bazarov even wedges himself between Arkady and his father, a man of nobility who loves and wills nothing but happiness upon his treasured son. However, the relationship between classmates deteriorates as the two young men enter the real world. The first subtle altercation occurring when Bazarov mocks Arkady’s father, behind his back, for proficiently playing the cello, laughing at the absurd idea of the old man wasting his time upon romantic artistic expression. More and more, Arkady comprehends his friend is a cold selfish being, one distant from others, unable to love or humble himself. Bazarov, the bold genius, in real life creates only complications and separation between individuals. Negatively, he isolates other characters, intently and critically attempting to undermine their beliefs in life, while all the time never having anything greater in mind. Deconstruction is an end in itself. I think of Nietzche descending into madness, never able to live a fruitful life rich in human relationships, his immensity of thought and reasoning inspiring the Nazis, and hence the brilliance of Bela Tarr’s brutal black and white film ‘The Turin Horse’. There is more to say and understand, yet I will let this quote stand on its own. It is a busy morning and I must get my day started.

It was midday. The sun was burning hot behind a thin veil of unbroken whitish clouds. Everything was hushed; there was no sound but the cocks crowing irritably at one another in the village, producing in every one who heard them a strange sense of drowsiness and ennui; and somewhere, high up in a tree-top, the incessant plaintive cheep of a young hawk. Arkady and Bazarov lay in the shade of a small haystack, putting under themselves two armfuls of dry and nestling, but still greenish and fragrant grass.

‘That aspen-tree,’ began Bazarov, ‘reminds me of my childhood; it grows at the edge of the clay-pits where the bricks were dug, and in those days I believed firmly that that clay-pit and aspen-tree possessed a peculiar talismanic power; I never felt dull near them. I did not understand then that I was not dull, because I was a child. Well, now I’m grown up, the talisman’s lost its power.’

‘How long did you live here altogether?’ asked Arkady.

‘Two years on end; then we travelled about. We led a roving life, wandering from town to town for the most part.’

‘And has this house been standing long?’

‘Yes. My grandfather built it, my mother’s father. ‘

‘Who was he—your grandfather?’

‘Devil knows. Some second-major. He served with Suvorov, and was always telling stories about the crossing of the Alps—inventions probably.’

‘You have a portrait of Suvorov hanging in the drawing-room. I like these dear little houses like yours; they’re so warm and old-fashioned; and there’s always a special sort of scent about them.’

‘A smell of lamp-oil and clover,’ Bazarov remarked, yawning. ‘And the flies in those dear little houses…. Faugh!’

‘Tell me,’ began Arkady, after a brief pause, ‘were they strict with you when you were a child?’

‘You can see what my parents are like. They’re not a severe soft.’

‘Are you fond of them, Yevgeny?’

‘I am, Arkady.’

‘How fond they are of you!’

Bazarov was silent for a little, ‘Do you know what I’m thinking about?’ he brought out at last, clasping his hands behind his head.

No. What is it?’

‘I’m thinking life is a happy thing for my parents. My father at sixty is fussing around, talking about ‘palliative” measures, doctoring people, playing the bountiful master with the peasants—having a festive time, in fact; and my mother’s happy too; her day’s so chockful of duties of all sorts, and sighs and groans that she’s no time even to think of herself; while I …’

‘While you?’

‘I think; here I lie under a haystack…. The tiny space I occupy is so infinitely small in comparison with the rest of space, in which I am not, and which has nothing to do with me; and the period of time in which it is my lot to live is so petty beside the eternity in which I have not been, and shall not be…. And in this atom, this mathematical point, the blood is circulating, the brain is working and wanting something…. Isn’t it loathsome? Isn’t it petty?’

‘Allow me to remark that what you’re saying applies to men in general.’

‘You are right,’ Bazarov cut in. ‘I was going to say that they now—my parents, I mean—are absorbed and don’t trouble themselves about their own nothingness; it doesn’t sicken them while I feel nothing but weariness and anger.’

‘Anger? why anger?’

‘Why? How can you ask why? Have you forgotten?’

‘I remember everything, but still I don’t admit that you have any right to be angry. You’re unlucky, I’ll allow, but …’

‘Pooh! then you, Arkady Nikolaevitch, I can see, regard love like all modern young men; cluck, cluck, cluck you call to the hen, but if the hen comes near you, you run away. I’m not like that. But that’s enough of that. What can’t be helped, it’s shameful to talk about.’ He turned over on his side. ‘Aha! there goes a valiant ant dragging off a half-dead fly. Take her, brother, take her! Don’t pay attention to her resistance; it’s your privilege as an animal to be free from the sentiment of pity—make the most of it —not like us conscientious self-destructive animals!’

‘You shouldn’t say that, Yevgeny! When have you destroyed yourself?’

Bazarov raised his head. ‘That’s the only thing I pride myself on. I haven’t crushed myself, so a woman can’t crush me. Amen! It’s all over! You shall not hear another word from me about it.’

Both the friends lay for some time in silence.

‘Yes,’ began Bazarov, ‘man’s a strange animal. When one gets a side view from a distance of the dead-alive life our “fathers” lead here, one thinks, What could be better? You eat and drink, and know you are acting in the most reasonable, most judicious manner. But if not, you’re devoured by ennui. One wants to have to do with people if only to abuse them.’

‘One ought so to order one’s life that every moment in it should be of significance,’ Arkady affirmed reflectively.

‘I dare say! What’s of significance is sweet, however mistaken; one could make up one’s mind to what’s insignificant even. But pettiness, pettiness, that’s what’s insufferable.’

‘Pettiness doesn’t exist for a man so long as he refuses to recognize it.’

‘Hmm what you’ve just said is a common-place reversed.’

‘What? What do you mean by that term?’

‘I’ll tell you; saying, for instance, that education is beneficial, that’s a common-place; but to say that education is injurious, that’s a common-place turned upside down. There’s more style about it, so to say, but in reality it’s one and the same.’

‘And the truth is—where, which side?’

‘Where? Like an echo I answer, Where?’

‘You’re in a melancholy mood to-day, Yevgeny.’

‘Really? The sun must have softened my brain, I suppose, and I can’t stand so many raspberries either. ‘

‘In that case, a nap’s not a bad thing,’ observed Arkady.

‘Certainly; only don’t look at me; every man’s face is stupid when he’s asleep.’

‘But isn’t it all the same to you what people think of you?’

‘I don’t know what to say to you. A real man ought not to care; a real man is one whom it’s no use thinking about, whom one must either obey or hate.’

‘It’s funny! I don’t hate anybody,’ observed Arkady, after a moment’s thought.

‘And I hate so many. You are a soft-hearted, mawkish creature; how could you hate any one? .. You’re timid; you don’t rely on yourself much.’

‘And you,’ intenupted Arkady, ‘do you expect much of yourself? Have you a high opinion of yourself?’

Bazarov paused. ‘When I meet a man who can hold his own beside me,’ he said, dwelling on every syllable, ‘then I’ll change my opinion of myself. Yes, hatred! You said, for instance, to-day as we passed our bailiff Philip’s cottage—it’s the one that’s so nice and clean—well, you said, Russia will come to perfection when the poorest peasant has a house like that, and every one of us ought to work to bring it about…. And I felt such a hatred for this poorest peasant, this Philip or Sidor, for whom I’m to be ready to jump out of my skin, and who won’t even thank me for it and why should he thank me? Why, suppose he does live in a clean house, while the nettles are growing out of me,—well what do I gain by it?’

‘Hush, Yevgeny if one listened to you today one would be driven to agreeing with those who reproach us for want of principles.’

‘You talk like your uncle. There are no general principles—you’ve not made out that even yet! There are feelings. Everything depends on them.’

‘How so?’

‘Why, I, for instance, take up a negative attitude, by virtue of my sensations; I like to deny—my brain’s made on that plan, and that’s all about it! Why do I like chemistry? Why do you like apples? by virtue of our sensations. It’s all the same thing. Deeper than that men will never penetrate. Not every one will tell you that, and, in fact, I shan’t tell you so another time.’

‘What? and is honesty a matter of the senses?’

‘I should rather think so.’

‘Yevgeny!’ Arkady was beginning in a dejected voice

‘Well? What? Isn’t it to your taste?’ broke in Bazarov. ‘No, brother. If you’ve made up your mind to mow down everything, don’t spare your own legs. But we’ve talked enough metaphysics. “Nature breathes the silence of sleep,” said Pushkin.’

‘He never said anything of the sort,’ protested Arkady.

‘Well, if he didn’t, as a poet he might have—and ought to have said it. By the way, he must have been a military man.’

‘Pushkin never was a military man!’

‘Why, on every page of him there’s, “To arms! to arms! for Russia’s honor!”‘

‘Why, what stories you invent! I declare, it’s positive calumny.’

‘Calumny? That’s a mighty matter! What a word he’s found to frighten me with! Whatever charge you make against a man, you may be certain he deserves twenty times worse than that in reality.’

‘We had better go to sleep,’ said Arkady, in a tone of vexation.

‘With the greatest pleasure,’ answered Bazarov. But neither of them slept. A feeling almost of hostility had come over both the young men. Five minutes later, they opened their eyes and glanced at one another in silence.

‘Look,’ said Arkady suddenly, ‘a dry maple leaf has come off and is falling to the earth; its movement is exactly like a butterfly’s flight. Isn’t it strange? Gloom and decay like brightness and life.’

‘Oh, my friend, Arkady Nikolaitch!’ cried Bazarov, ‘one thing I entreat of you; no fine talk.’

‘I talk as best I can…. And, I declare, its perfect despotism. An idea came into my head; why shouldn’t I utter it?’

‘Yes; and why shouldn’t I utter my ideas? I think that fine talk’s positively indecent.’

‘And what is decent? Abuse?’

‘Ha! ha! you really do intend, I see, to walk in your uncle’s footsteps. How pleased that worthy imbecile would have been if he had heard you!’

‘What did you call Pavel Petrovitch?’

‘I called him, very justly, an imbecile.’

‘But this is unbearable!’ cried Arkady.

‘Aha! family feeling spoke there,’ Bazarov commented coolly. ‘I’ve noticed how obstinately it sticks to people. A man’s ready to give up everything and break with every prejudice; but to admit that his brother, for instance, who steals handkerchiefs, is a thief—that’s too much for him. And when one comes to think of it: my brother, mine—and no genius that’s an idea no one can swallow.’

‘It was a simple sense of justice spoke in me and not in the least family feeling,’ retorted Arkady passionately. ‘But since that’s a sense you don’t understand, since you haven’t that sensation, you can’t judge of it.’

‘In other words, Arkady Kirsanov is too exalted for my comprehension. I bow down before him and say no more.’

‘Don’t, please, Yevgeny; we shall really quarrel at last.’

‘Ah, Arkady! do me a kindness. I entreat you, let us quarrel for once in earnest….’

‘But then perhaps we should end by …’

‘Fighting?’ put in Bazarov. ‘Well? Here, on the hay, in these idyllic surroundings, far from the world and the eyes of men, it wouldn’t matter. But you’d be no match for me. I’ll have you by the throat in a minute. ‘

Bazarov spread out his long, cruel fingers…. Arkady turned round and prepared, as though in jest, to resist…. But his friend’s face struck him as so vindictive—there was such menace in grim earnest in the smile that distorted his lips, and in his glittering eyes, that he felt instinctively afraid.

‘Ah! so this is where you have got to!’ the voice of Vassily Ivanovitch was heard saying at that instant, and the old army-doctor appeared before the young men, garbed in a home-made linen pea-jacket, with a straw hat, also home-made, on his head. ‘I’ve been looking everywhere for you…. Well, you’ve picked out a capital place, and you’re excellently employed. Lying on the “earth, gazing up to heaven.” Do you know, there’s a special significance in that?’