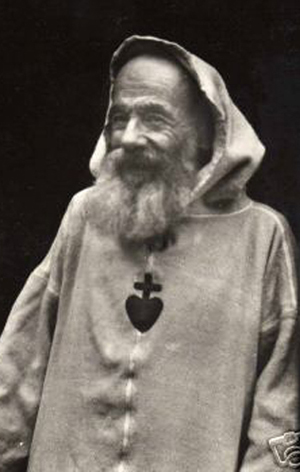

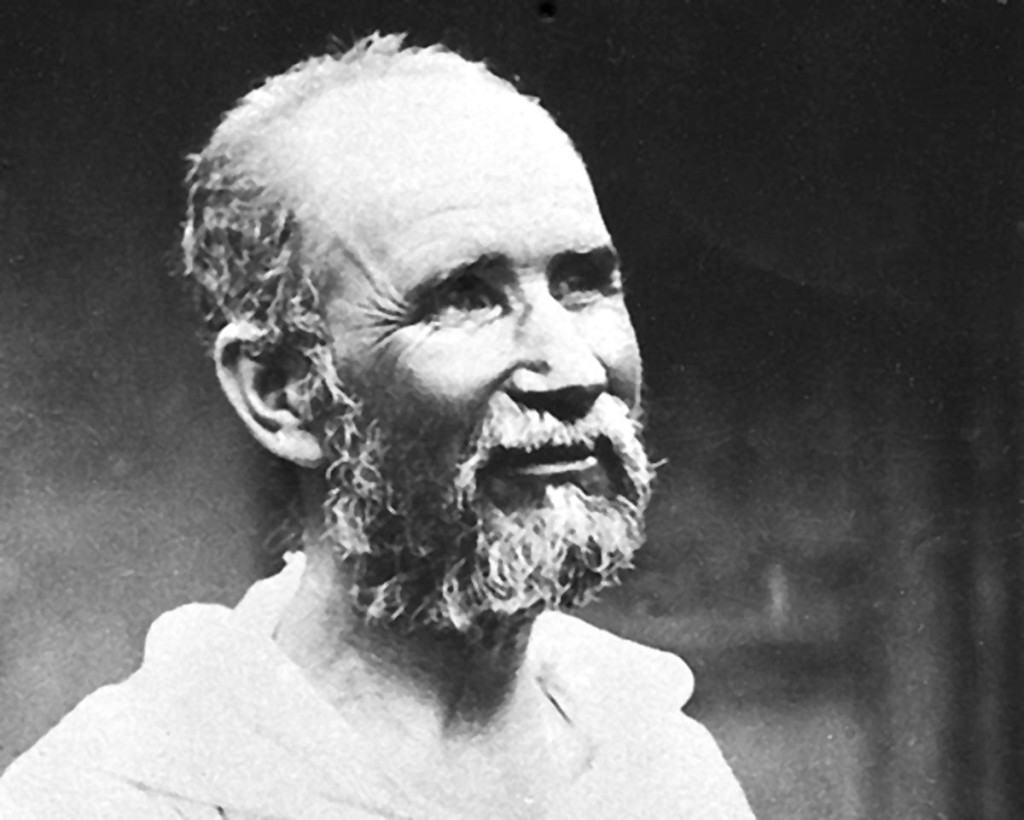

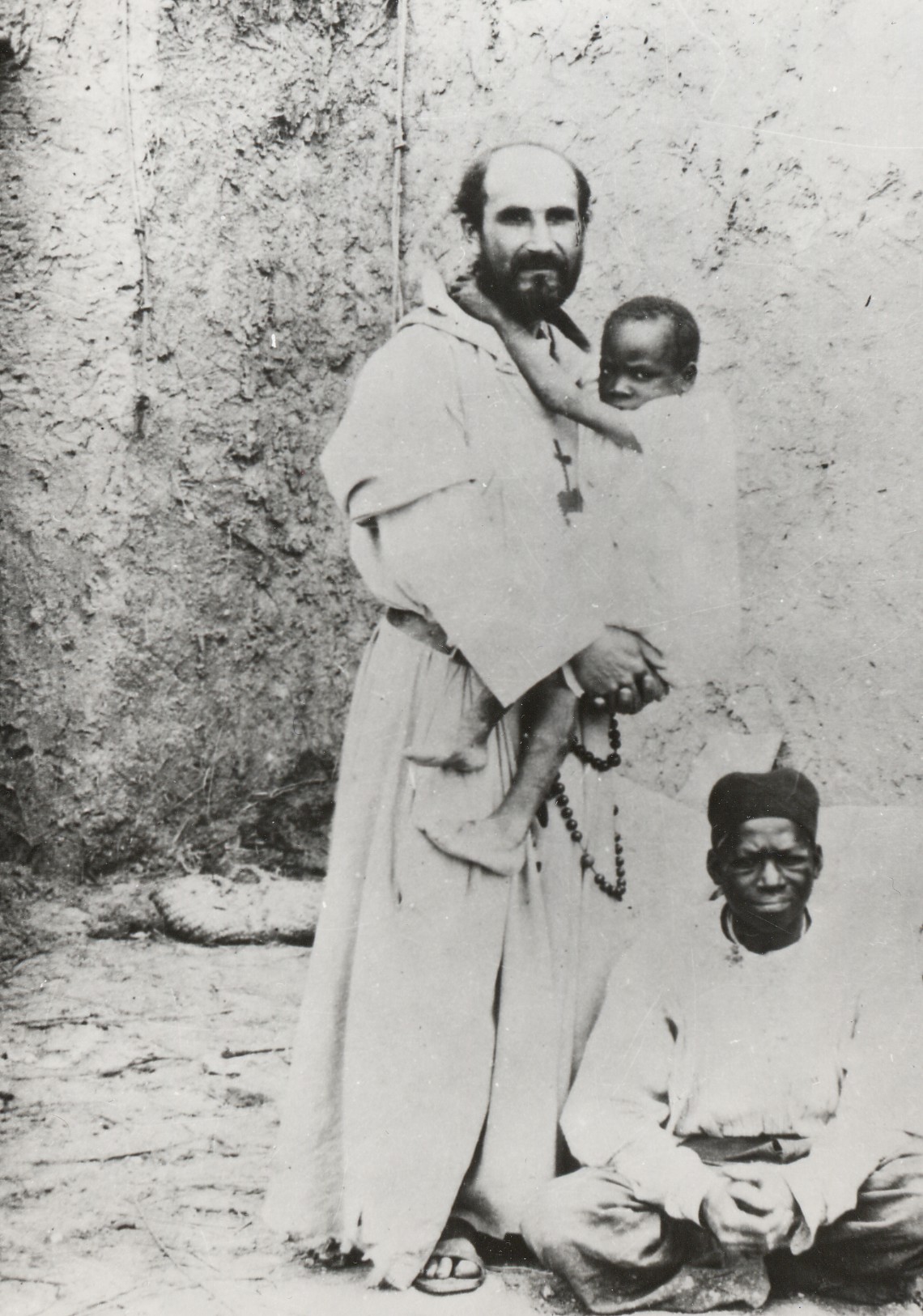

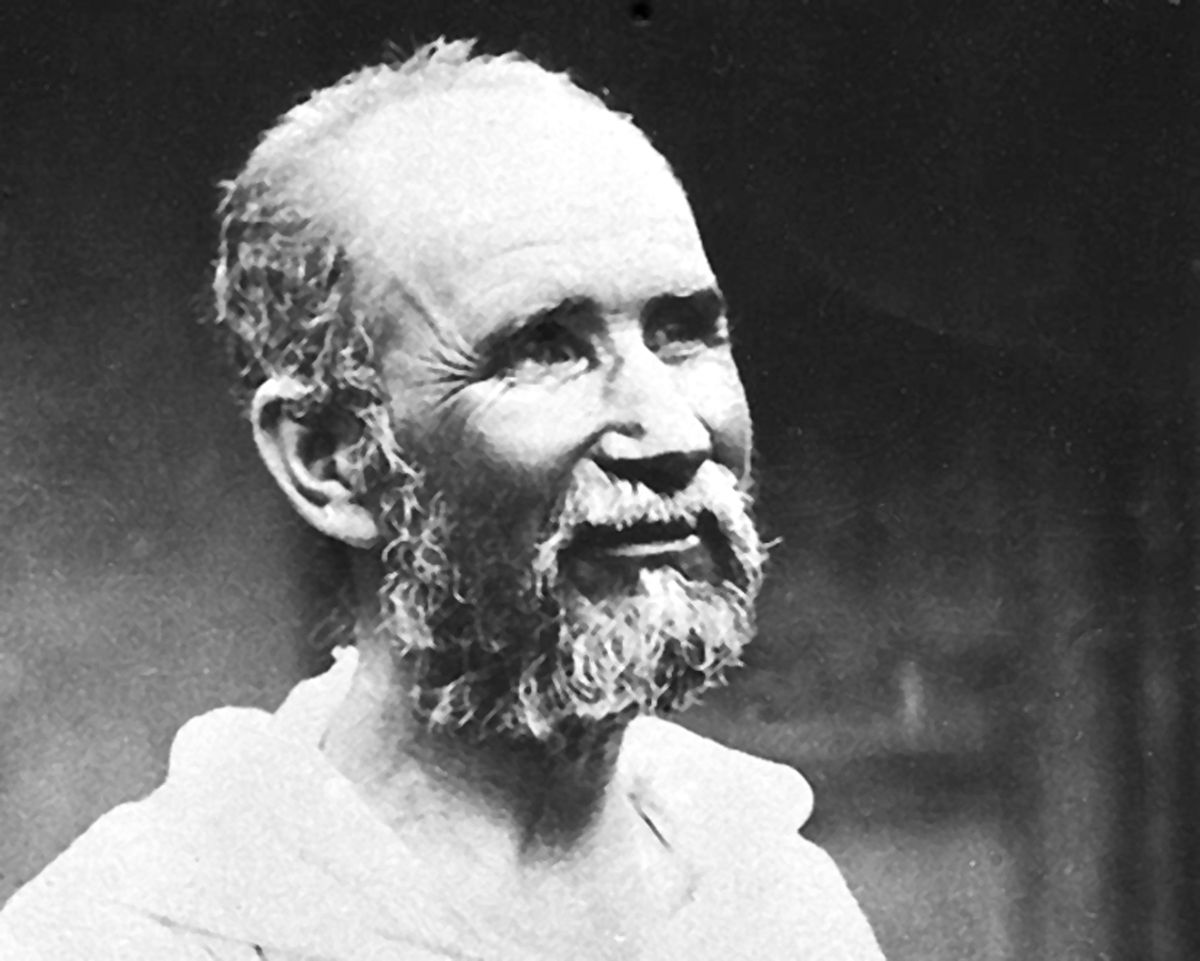

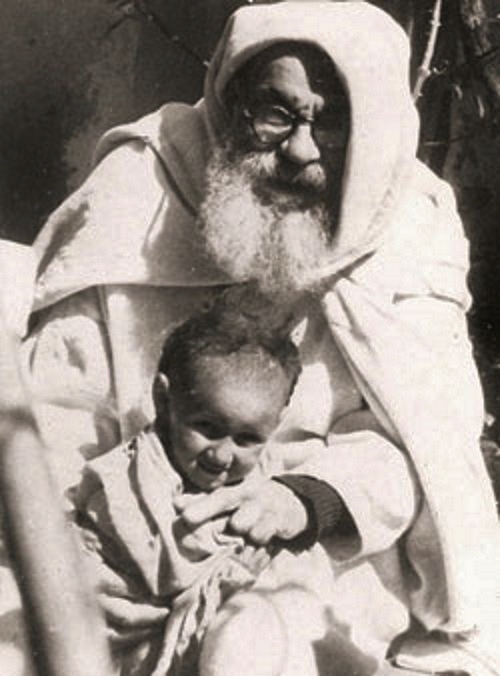

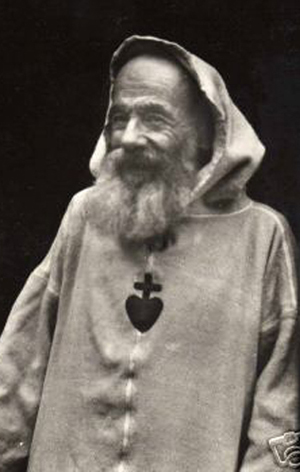

I have noticed my reading has centered upon a French spirituality. Father Thomas Philippe amazes, stunning in relevancy, broadening and deepening contemplative ideas. I am also completing a St Paschal Baylon Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament priest’s biography on St Peter Julian Eymard. Then there is the comical desert tramp Charles de Foucald, always ripe for the pleasing. Another Frenchman, another Sahara desert dweller, I also discovered while in North Dakota, Father Albert Peyriguere, a devotee of Foucauld. Father Peyriguere’s writing is in the tradition of two French religious, St Francis de Sales and St Jane de Chantal, that is spiritual direction through the exchanging of letters. The poignancy of Father Peyriguere’s writing is his ability, similar to Father Philippe, in advancing contemplative ideals beyond the idealistic. He pulverizes concepts while actively pursuing his individual path through the directing of another. Demonstrating the contemplative life is not a matter of knowledge, nor a silly self-consumed game of superior and inferior, a need to surround one’s self with weakness in order to feel comfortable in spiritual preeminence. The contemplative life is not a game, an intellectual pursuit, nor a social activity. The only way properly done, it is not of our doing. A deeper introspective spiritual life is more than learning concepts espoused by saints. It is more than articulating phenomenal spiritual acumen. I will quote my own writing, words from a young man: Damn this random effort and too many books. It is time to throw away your books, and all your puerile words you thrust at others as if they were daggers, sharpened for stabbing, victory for attaining. Quit vomiting all over yourself, and leave others alone. And what about the writing you do manage to accomplish, you treat every word with such a reverence…it’s disgusting…and the truths you do manage to conclude through reasoning…well, I never. I do not understand this behavior, as a matter of fact I find it despicable. You are an intellectual old man while not advancing and that is a stagnating state. Let go, unlearn, release and unwind, slowdown in order to be like a child. I’ll tell you what to do, interiorly evolve to the point you are able to smash your conclusions, affirm a reality, a truth if you need to call it that, and then be done with it and throw it aside. Avoid dwelling upon your conclusions for you will only warp reality into your personal perversion. Through the centuries, the world has been polluted enough. Ideas like the dark night of the soul, detachment, abandonment, contemplation, meditation become absurd in spiritual fantasy, minds scheming and dreaming attain an absurd status within imaginary perfection. Father Peyriguere, advising a seasoned nun, is acute in penetrating through a dedicated spiritual life failing in regards to advancement exceeding decades of practice.

What pleasure you gave me when you wrote that your life is “simplified”, calmed and illumined.” It was so complicated, so involved, so tense and tormented, so befogged with book learning. But we cannot stop struggling when deep within us there remains a bit of ourselves; or, to put it another way, since we must never look at ourselves even to deny ourselves, as long as we are not solely Christ. But you may still be looking for Christ outside of yourself, far from you, as for someone you want to draw towards you.

You are still trying to go to Christ in two stages: 1) You leave yourself, displeased with self, disapproving of and denying self. 2) You try to bring Christ in.

Proper means of unification: 1) You empty yourself. 2) You let Christ fill the void.

This is still too complicated. The trouble with this system is that in the long run, by being continually confronted with our faults and failings, we may grow tired and depressed and, at the same time we may minimize the part played by Christ in us, it is our doing, when really we had nothing to do with it.

Christ is not captured, is not conquered. We allow Him to come in and expose ourselves to Him. We do not take possession of Him, He he takes possession of us. –Father Albert Peyriguere ‘Voice from the Desert’

Final note. Speaking of not doing things myself, I am recognizing it as a good thing, yet my new employment does not allow internet access while working, plus we stay constantly busy. I love being challenged at work, continually on the go or learning. Labor makes for a prosperous spiritual life, humbling and demanding accountability. My telephone service is minimal while in the building, internet accessibility nulled. I will only be making post first thing in the morning during work days. Tomorrow, a slow time in coming—to me a sign of the workings of God, I will finally attend training for the Hospice of Western Reserve, eight hours in commencing. Something within the happening soothes interiorly.

Recent Comments