“Love consists not in feeling great things,” says St. John of the Cross, “but in having great detachment and in suffering for the Beloved,”

In some way, one must develop the habit of going from a mental activity, corresponding to our clear awareness, to what we feel, what we mentally recall, imagine, sense in our body or in our psyche, to a spiritual life where everything is apparently abolished.

This transfer is not easy: it is but a variation on the theme which is central to our study, the descent from Jerusalem to Nazareth; Jerusalem, the image of mental life as “religious” as one could wish, as rich as one could hope, and Nazareth, the image of a spiritual life, detached, silent, obscure. No, this transfer is not easy but, fortunately, as the angel said, “Nothing is impossible with God” (cf Lk 1:37).

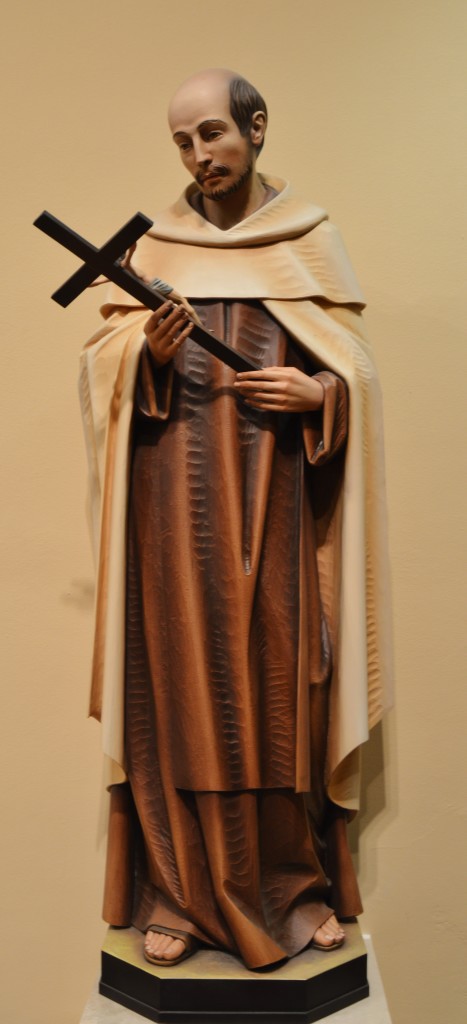

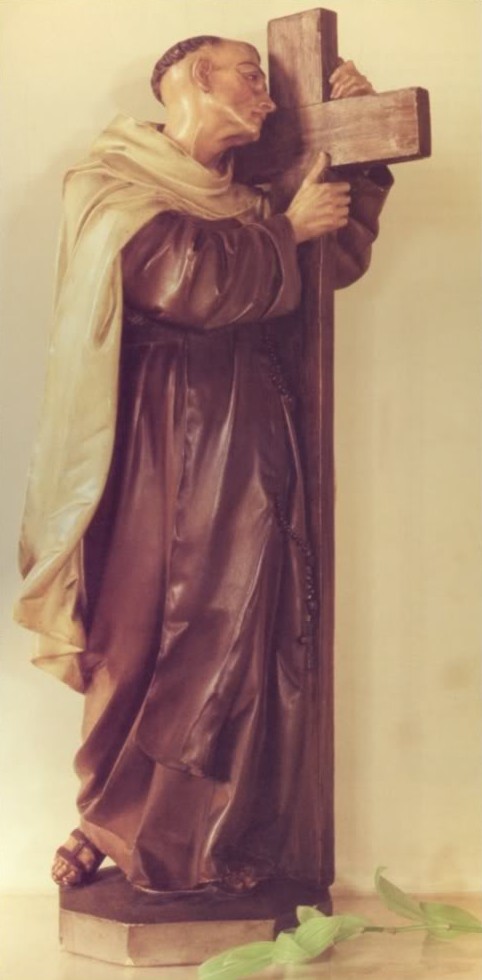

When one senses his presence, thanks to Mary, Joseph appears to me to be the master of this delicate transfer.

People will perhaps be surprised to know that I do not often address prayers to Joseph, while I am deeply aware that I pray only in him. I do think of him (what could my thinking be focused on?) but he teaches me, precisely, the art of not thinking “in the human way,” a way which so often saddened Jesus when he was with his apostles (cf Mt 16:23).

Let us consider an example: the more someone is dear to us, the less we have to think of that person. We must reach him on a spiritual level whether he is present or absent, and not through imagination, daydreams or a set of impressions we interpose. The mental faculty must be at the service of the operation with the greatest discretion possible: it must not act as a screen, capturing, our arresting, and all the more so, distorting. We must realize that unless a kind of miracle takes place, things are bound to be so.

The human mental faculty is intrusive and, moreover, it is falsified most of the time, except in a tiny child and in those who end up by being like children after a long period of purification. Never were Jesus’ words so true: “No one is good but God alone!” (Lk 18:19). Human imagination, memory, feelings and the rest are a field of darnel dramatically mixed up with the good grain and it is preferable that we leave it so, as Jesus says. The more the affective aspect of our nature is unleased in what we call love or its opposites (anger, indignation, jealousy, fear, etc.), the more the mental aspect becomes delirious, tyrannical, dangerous, the more it risks falsifying objective reality.

What shall we say about fixed ideas, obsessions and other analogous difficulties which are so dramatically widespread?

Joseph teaches us the supreme art of dying to our mental life in order to allow ourselves to be born again to a way of perfection which is akin to that of Mary and is only remotely similar to what we could have known previously. Let us, for some time, try the experiment of never deliberately recalling the human being we love very much; we will then begin to realize that love comes from much beyond, from a much greater depth than our human heart alone, our feelings, our judgment, whatever qualities they may have. We will experience a freedom so new, an insight, a loving force so ingenious that we will no longer be able to deny that all comes from elsewhere.

St. John of the Cross, this accomplished son of the Carmel of the house of Mary and Joseph, had said as much but it was difficult to believe him.

“Take no heed of the creatures if thou wilt keep the image of God clearly and simply in thy soul, but empty thy spirit of them, and withdraw far from them, and thou shalt walk in the Divine light, for God is not like to the creatures.”

‘Saint Joseph: Shadow of the Father’ written by Father Andrew Doze

Recent Comments