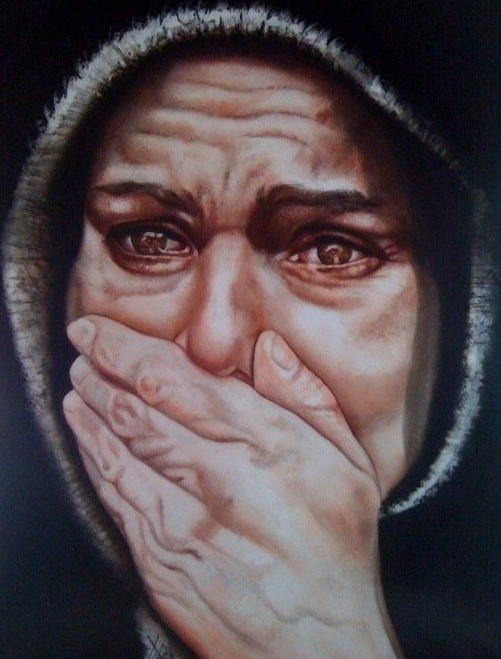

One must not exaggerate and squander one’s strength in the excess of conquering force. The generous man tends to move forward too fast: he wants to restore the good and destroy the injustice. But there is inertia in both men and things that he must take into account. Mystically, it is a matter of walking in step with God, of fitting exactly into the plan of God.

All effort to move faster than God is useless, and even worse, harmful. Activity is replaced by activism, which goes to the head like champagne, aspires to unreachable goals and leaves no time for contemplation. A man is no longer master of his life: the danger of excess of action is compensation. An exhausted man easily seeks it. This is all the more dangerous when one has to some extent lost self-control.

The body is tired, the nerves are agitated, the will vacillating. The greatest stupidities are possible in these moments. One simply has to slow down, find one’s call again among true good friends, recite one’s Rosary mechanically and fall asleep sweetly in the Lord. –St Albert Hurado

God is a challenging and invigorating voice of unpredictability, wise in knowing what is best. I rose this morning early to attend a pre-mass Rosary and Divine Mercy communal prayer at St Clare, focused upon my Hospice patient, preparing for my morning afternoon bedside visit. The communal prayer did not work. The participants praying so fast and self-consciously I could not absorb myself. There was no recourse except silence. Mass concluded, Eucharist received, the reading of David slaying Goliath always providing wonder. A voice mail waited on my phone. It was the Hospice. The patient passed away at four in the morning. They would not be needing my service. She did not wait for me. I felt stung by pride. God demonstrating he did not need me to advance the woman to eternal peace. I needed the woman and the thought of doing something spiritually superior. God wanted me to go home and take a nap. The above quote came from the autobiography of Abbot William from the Maronite Monks of Adoration. Abbot’s thoughts were important. I am not going to put them together, pointing out relevancy with words and ideas: disjointed, masks, multiple personalities, anxiety, nature building upon grace, proper rest. My Holy Hour after mass I could barely stay awake, fighting sleep, deeply exhausted. My late night vigils, overload of Hospice calls, and seven days of work caught up with me. Driving home, John the Hermit called. We have not talked in days. He stressed the difference between our nervous systems functioning in a sympathetic or parasympathetic mode—bottom line: living a life of reaction to worldly concerns opposed to a life of contemplation and absorption in God. He takes it much deeper, encompassing a holistic understanding of one’s life and personal habits. He said to go home and get some rest. Everything coalesced, further words from Abbot William arising in poignancy, tantalizing in indirectly teasing toward the consecrated life, while eluding to the neurosis of modern city life. It all comes together within mystery. The title of the book: ‘A Calling: An Autobiography’.

An old colloquialism comes to mind: “You can take the boy out of the country, but you can’t take the country of the boy.” In the old European formula, the average Catholic vocation in Europe came from farm and country. He knew farm life; he knew how it worked. He knew the soil. He knew a sick cow from a healthy one. He knew the land and how and when to hay.

On the American scene, we meet the obverse: “You can take the boy out of the city but you can’t take the city of the boy.” The average candidate for an American monastery came from the city, suburbia, a college campus, or the armed services. His whole culture and economic arrangement was ‘punching the clock’. He worked his forty hour week, and when he was finished, it was done. He received his wages and went home. His skill and expertise were to be all efficient and he was to expedite the work. If he was a hustler, he was considered an efficient worker. This habit and mentality was ingrained in him.

In agrarian society, however, the work on the farm is never done. One did not punch the clock on the farm. The chores were always there, all day long, seven days a week. The farmer handled his task and survived by his ability to work his farm at a ‘farmer’s pace’. The farm candidate brought that particular culture and manner of living to the monastery. The old Trappist regime was constructed around the old world agrarian society. The Trappist monk could be very contemplative within the context of living the old Trappist structure—at a farmer’s pace. But this, quite obviously, was not so readily accomplished on the American scene.

Recent Comments