Stanzas From The Grand Chartreuse

a poem by Matthew Arnold

Through Alpine meadows soft-suffused

With rain, where thick the crocus blows,

Past the dark forges long disused,

The mule-track from Saint Laurent goes.

The bridge is cross’d, and slow we ride,

Through forest, up the mountain-side.

….

The autumnal evening darkens round,

The wind is up, and drives the rain;

While, hark! far down, with strangled sound

Doth the Dead Guier’s stream complain,

Where that wet smoke, among the woods,

Over his boiling cauldron broods.

…

Swift rush the spectral vapours white

Past limestone scars with ragged pines,

Showing—then blotting from our sight!—

Halt—through the cloud-drift something shines!

High in the valley, wet and drear,

The huts of Courrerie appear.

…

Strike leftward! cries our guide; and higher

Mounts up the stony forest-way.

At last the encircling trees retire;

Look! through the showery twilight grey

What pointed roofs are these advance?—

A palace of the Kings of France?

…

Approach, for what we seek is here!

Alight, and sparely sup, and wait

For rest in this outbuilding near;

Then cross the sward and reach that gate.

Knock; pass the wicket! Thou art come

To the Carthusians’ world-famed home.

…

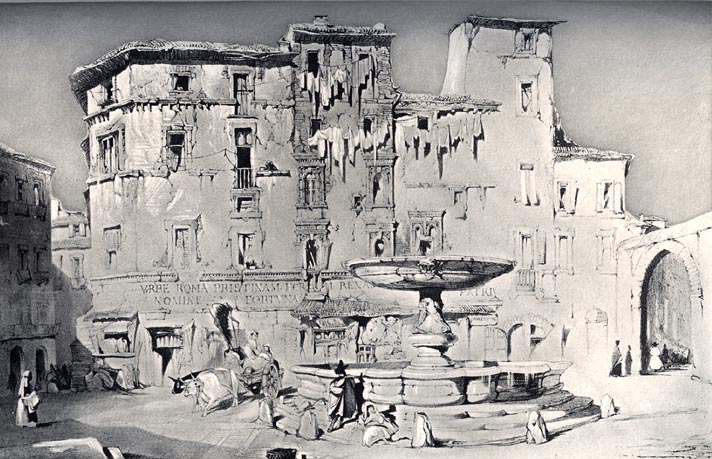

The silent courts, where night and day

Into their stone-carved basins cold

The splashing icy fountains play—

The humid corridors behold!

Where, ghostlike in the deepening night,

Cowl’d forms brush by in gleaming white.

…

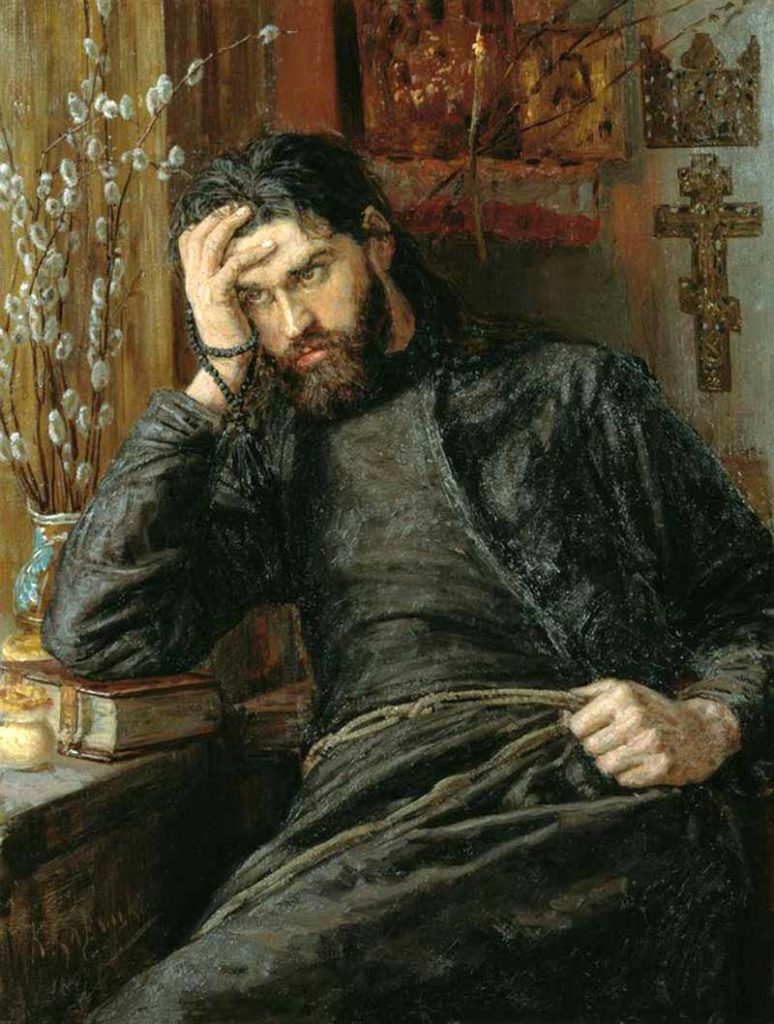

The chapel, where no organ’s peal

Invests the stern and naked prayer—

With penitential cries they kneel

And wrestle; rising then, with bare

And white uplifted faces stand,

Passing the Host from hand to hand;

…

Each takes, and then his visage wan

Is buried in his cowl once more.

The cells!—the suffering Son of Man

Upon the wall—the knee-worn floor—

And where they sleep, that wooden bed,

Which shall their coffin be, when dead!

…

The library, where tract and tome

Not to feed priestly pride are there,

To hymn the conquering march of Rome,

Nor yet to amuse, as ours are!

They paint of souls the inner strife,

Their drops of blood, their death in life.

…

The garden, overgrown—yet mild,

See, fragrant herbs are flowering there!

Strong children of the Alpine wild

Whose culture is the brethren’s care;

Of human tasks their only one,

And cheerful works beneath the sun.

…

Those halls, too, destined to contain

Each its own pilgrim-host of old,

From England, Germany, or Spain—

All are before me! I behold

The House, the Brotherhood austere!

—And what am I, that I am here?

…

Too be continued…..

Recent Comments