Wandering between two worlds, one dead,

The powerless to be born,

With nowhere yet to rest my head,

Like these, on earth I wait forlorn,

Their faith, my tears, the world derides—

I come to shed them at their side.

To keep himself (the poet Matthew Arnold) in countenance, he has to regard the Carthusians too as ghosts, unmanned men, half realities flitting between sheer nothingness and full-bodied life; they are, like himself, survivors—he, “last of the race of them who grieve”; they, last “of the people who believe.”

He has to set them besides himself, looking regretfully out at the life of action—he, spoilt for it by his corroding agnosticism, which is yet to find any satisfaction in any hard and gay materialism; they, because they can’t help themselves either: their “bent was taken long ago”; action and pleasure call them “too late”; they beg not to be disturbed, but to be left in reverie, shade, and desert peace.

Well, we must allow Matthew Arnold had to be melancholy, but really we can’t have him suggesting Carthusians are. It is perfectly true that ex-soldiers, ex-judges, ex-courtiers, ex-roues (a debauched man, especially an elderly one), are to be found in plenty within these cloisters; it is true, too, that they would say, looking back upon their old lives, it was, in a sense, “the vanity” which the ancient writer called it; but they wouldn’t allow that they had, by old experience or new self-oblation, lost anything. The gaiety of novitiates is proverbial, and the stricter the gayer,,,a weight has indeed been removed, it leaves a man freer and stronger to march, and gives him reasonable hopes of attaining. Really it is time that the old myth of cloisters filled with disillusioned men and jilted girls be given up. Postulants don’t go there out of pique, or to hide, or to pine, or to look backwards generally; but in the certainty of finding the positive, the substantial and the stimulating. Nor are they packed with cheated boys, “cooked vocations,” anemia and ignorant lads destined afterwards to look wistfully across the grilles at banners and bugles, pomp and pleasures, too little appreciated to cause more than the mildest stirring of their atrophied instincts. Carthusians do not, I dare say, laugh much, but I know they can smile, and very humoursly; and I fear they would be outright tempted to chaff the plaintive poet who came to beg permission to mingle his tears with theirs; the poet, lamenting that he had been forced to abandon much, and had got nothing in return; deploring even the high sacrifice and sorrows of others—a Byron’s, a Shelly’s, a Senancour’s, since no one was a bit the better for their effort and their pains….Sacrifice and sorrow are indeed, the Carthusians’ motto would confess, a world-abiding law, but they are quite sure they possess a life, so expansive and transcendent and unitive that there is no room for repining. The Cross stretches arms wide to embrace the universe; the agnostic frets and dwindles within the circle of himself. Stevenson, temperamentally very different than Matthew Arnold, yet sees the monks from somewhat the same angle. Frankly they are skulkers. He, with all the spirit of life pulsating in his brain, passes too “out of the sun,” out of reach of lute and fife, rumor of the world at large, and holier realm of “confidences low and dear.” There, at “Our Lady of the Sorrows,” he finds the “unfraternal brothers,” “aloof, unhelpful and unkind, the prisoners of the iron mind”—

Poor passionate men, still clothed afresh

With agonizing folds of flesh;

Whom the clear eyes solicit still

To some bold output of the will.

Fancy and Memory conspire to call them, and him, “to heroic death,” or to “uncertain fresh delight.” To the “uproar and the press,” to “human business,” to laughter, honor, fight and failure and new flight, he summons them from their “prudent turret and redoubt.” God, spying from Heaven’s a top “the noble wars“ of mankind, shall like enough “pass their corner by”—

For still the Lord is Lord of might,

In deeds, in deeds, He takes delight.

The plough, spear, ship, city; the streets, the fields; the climber, the songster; the unfrowning “Caryatides” (a stone carving of a draped female figure, used as a pillar to support the entablature of a Greek or Greek-style building) who by their “daily virtues,” weaken enough, no doubt, yet “under-prop” high Heaven; trade, marriage, motherhood; the sowers of gladness—these He will approve.

But ye! O ye who linger still

Here in your fortress on the hill

With placid face, with tranquil breath,

The unsought volunteers of death,

Our cheerful General on high

With careless looks may pass you by.

–C.C. Martindale ‘Upon God’s Holy Hills: The Guides St. Anthony Of Egypt, St. Bruno of Cologne, St. John Of The Cross’

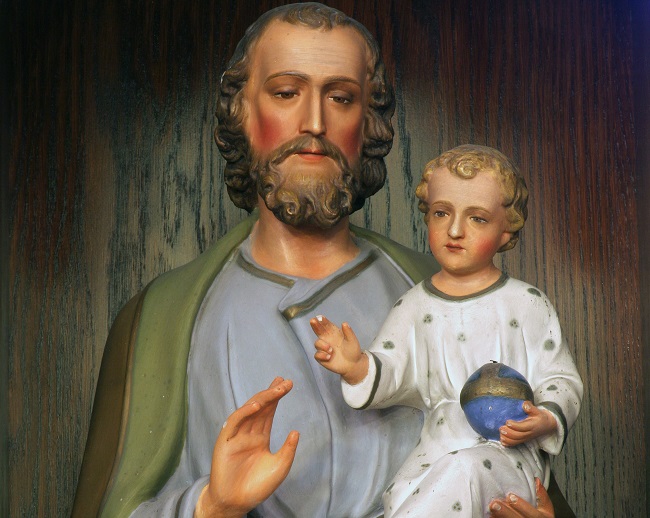

An image of St Teresa from an interesting contemporary artist in New Mexico

An image of St Teresa from an interesting contemporary artist in New Mexico

Recent Comments