Prayer is both a gift of grace and a determined response on our part. It always presupposes effort. The great figures of prayer of the Old Covenant before Christ, as well as the Mother of God, the saints, and he himself, all teach us this: prayer is a battle. Against whom? Against ourselves and against the wiles of the tempter who does all he can to turn man away from prayer, away from union with God. We pray as we live, because we live as we pray. If we do not want to act habitually according to the Spirit of Christ, neither can we pray habitually in his name. The “spiritual battle” of the Christian’s new life is inseparable from the battle of prayer.

………………..

We must also face the fact that certain attitudes deriving from the mentality of “this present world” can penetrate our lives if we are not vigilant. For example, some would have it that only that is true which can be verified by reason and science; yet prayer is a mystery that overflows both our conscious and unconscious lives. Others overly prize production and profit; thus prayer, being unproductive, is useless. Still others exalt sensuality and comfort as the criteria of the true, the good, and the beautiful; whereas prayer, the “love of beauty” (philokalia), is caught up in the glory of the living and true God. Finally, some see prayer as a flight from the world in reaction against activism; but in fact, Christian prayer is neither an escape from reality nor a divorce from life.

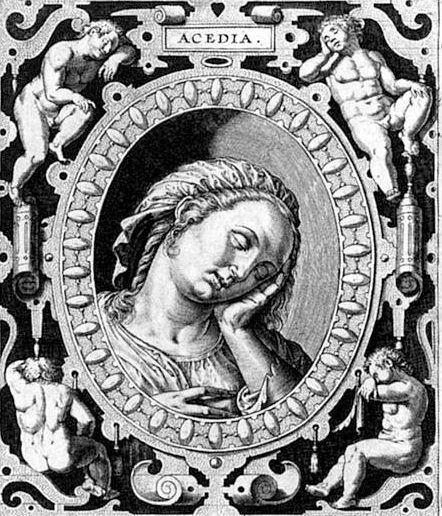

Another temptation, to which presumption opens the gate, is acedia. The spiritual writers understand by this a form of depression due to lax ascetical practice, decreasing vigilance, carelessness of heart. “The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.” The greater the height, the harder the fall. Painful as discouragement is, it is the reverse of presumption. The humble are not surprised by their distress; it leads them to trust more, to hold fast in constancy. –Catechism of the Catholic Church

Evagrius of Pontus: The demon of acedia, which is also called the noonday demon, is the most burdensome of all the demons. It besets the monk at about the fourth hour (10 am) of the morning, encircling his soul until about the eighth hour (2 pm). First it makes the sun seem to slow down or stop moving , so that the day appears to be fifty hours long. Then it makes the monk keep looking out of his window and forces him to go bounding out of his cell to examine the sun to see how much longer it is to 3 o’clock, and to look round in all directions in case any of the brethren is there. Then it makes him hate the place and his way of life and his manual work. It makes him think that there is no charity left among the brethren; no one is going to come and visit him. If anyone has upset the monk recently, the demon throws this in too to increase his hatred. It makes him desire other places where he can easily find all that he needs and practice an easier, more convenient craft. After all, pleasing the Lord is not dependent on geography, the demon adds; God is to be worshipped everywhere. It joins to this the remembrance of the monk’s family and his previous way of life, and suggests to him that he still has a long time to live, raising up before his eyes a vision of how burdensome the ascetic life is. So, it employs, as they say, every [possible] means to move the monk to abandon his cell and give up the race. No other demon follows on immediately after this one but after its struggle the soul is taken over by a peaceful condition and by unspeakable joy.

*******************

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, for example, sloth is described as tepid love, the failure to love God with all of one’s being (lento amore). In the popular imagination sloth has become equivalent to laziness, yet the Eastern Christian understanding of acedia enjoys a much richer meaning. Acedia, says Evagrius, is the “noon-day demon” that attacks the believer when the sun is at its highest and the heat unbearably oppressive. It is more than a flaw of character but an alien power that drains the person of energy and life, ultimately leading to spiritual death and sometimes even suicide, tearing “the soul to pieces as a hunting-dog does a fawn”.

The eight logismoi (temptations) of Evagrius combine in various ways, generating different psychic-spiritual outcomes; but acedia appears to be unique in one respect: “If it is true that, for the others, at any given time they are a link in a colorful and variously assembled chain (God’s creation), so it is said of despondency that it is always the terminus (the end of faith, hope, and love) of such a chain, and is therefore not followed immediately by any other ‘thoughts’”.

It’s as if acedia makes it impossible for the other passions to operate, so enervating is the gloom. For this reason Evagrius identifies acedia as “the most oppressive of all demons”. On the day that it strikes, “no other thought follows that of despondency, first because it persists, and then also, because it contains in itself nearly all the thoughts”. Hence it is one of the most dangerous of the vices and the most difficult to combat, especially if it settles into a more or less permanent condition. The frustration of desire, inevitably accompanied by anger, fuels the deadly torpidity. “A despondent person hates precisely what is available,” Evagrius writes, “and desires what is not available”. He is thus reduced to a state of irrationality, “dragged by desire and beaten by hatred”

………………..

Finally, a characteristic time factor may be added. The other thoughts come and go at times even very rapidly, for example those of impurity and blasphemy. In contrast, the thought of acedia, because of its complex nature, which unites in itself the most diverse other thoughts, has the characteristic of lasting for a long time. From that duration arises an entirely particular state of mind, such as is typical for depression. When it is not recognized in a timely manner, or rather when one refrains from applying the appropriate remedies, it can become more or less manifest as a permanent condition.

In the life of the soul, acedia thus represents a type of dead end. A distaste for all that is available combined with a diffuse longing for what is not available paralyzes the natural functions of the soul to such a degree that no single one of any of the other thoughts can gain the upper hand! —Eclectic Orthodoxy website reviewing the book ‘Despondency: The Spiritual Teaching of Evagrius of Pontus’ by Father Gabriel Bunge.