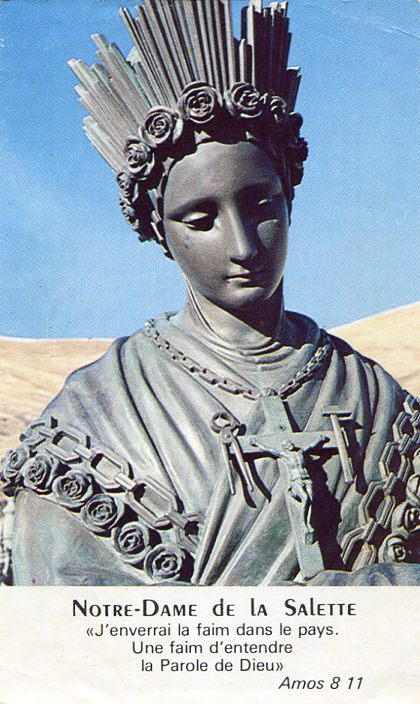

Huysmans continues the conversion of the French writer/aesthete Durtal in the novel ‘Cathedral’. The Cathedral referred to by the title is Chartres. Consecrated in 1260, in the presence of King St Louis, Chartres represents majestically to Durtal all that he pursues in his rejection of decadent modernism and the embracing of a profound Catholic medieval faith. A wearied cultured man, he reverses time in order to move forward spiritually. Appropriate with the anniversary of Fatima, Huysmans opens the second novel of the Durtal Trilogy with an examination of Our Lady’s apparition at the remote Alps town of La Salette, an apparition striking solely based upon foreshadowing similarities with Lourdes and Fatima. Huysmans writes in the most devoted manner of Our Lady. Keep in mind ‘Cathedral’ was written in 1898, before Fatima. Huysmans disturbing and grand descriptions of the geography surrounding La Salette proves spiritually revealing—a cryptic revelation.

He (Durtal) thought of the Virgin, whose watchful care had so often preserved him from unexpected risk, easy slips, or greater falls. Was not She the bottomless Well of goodness, the Bestower of the gifts of good Patience, the Opener of dry and obdurate hearts? Was She not, above all, the living and thrice Blessed Mother?

Bending forever over the squalid bed of the soul, she washes the sores, dresses the wounds, strengthening the fainting weakness of converts. Through all the ages She was the eternal supplicant, eternally entreated; at once merciful and thankful; merciful to the woes She alleviates, and thankful to them too. She was indeed our debtor for our sins, since, but for the wickedness of man, Jesus would never have been born under the corrupt semblance of our image, and She would not have been the immaculate Mother of God. Thus our woe was the first cause of Her joy; and this supremist good resulting from the very excess of Evil, this touching though superfluous bond, linking us to Her, was indeed the most bewildering of mysteries; for Her gratitude would seem unneeded, since Her inexhaustible mercy was enough to attach Her to us forever.

Thenceforth, in Her immense humility, She had at various times condescended to the masses; She had appeared in the most remote spots, sometimes seeming to rise from the earth, sometimes floating over the abyss, descending on solitary mountain peaks, bringing multitudes to Her feet, and working cures…

…On the 19th of September, 1846, the Virgin had appeared to two shepherd children on a hill; it was a Saturday, the day dedicated to Her, which, that year, was a fast day by reason of the Ember week. By another coincidence, this Saturday was the eve of the Festival of Our Lady of Seven Sorrows, and the first vespers were being chanted when Mary appeared as from a shell of glory just above the ground.

And she appeared as Our Lady of Tears in that desert landscape of stubborn rocks and dismal hills. Weeping bitterly, She had uttered reproofs and threats; and a spring, which never in the memory of man had flowed excepting at the melting of the snows, had never since been dried up.

The fame of this event spread far and wide; frantic thousands scrambled up fearful paths to a spot so high that trees could not grow there. Caravans of the sick and dying were conveyed, God knows how, across ravines to drink the water; and maimed limbs recovered, and tumors melted away to the chanting of canticles.

…there are no fir trees, no beeches, no pastures, no torrents; nothing—nothing but total solitude, and silence unbroken even by the cry of a bird, for at that height no bird is to be found.

“What a scene!” thought Durtal, calling up the memories of a journey (to La Salette) he had made with the Abbé Gévresin (spiritual director) and his housekeeper, since leaving La Trappe (‘En Route’ monastery). He remembered the horrors of a spot he had passed between Saint Georges de Commiers and La Mure, and his alarm in the carriage as the train slowly travelled across the abyss. Beneath was darkness increasing in spirals down to the vast deeps; above, as far as the eye could reach, piles of mountains invaded the sky.

The train toiled up, snorting and turning round and round like a top; then, going into a tunnel, was swallowed by the earth; it seemed to be pushing the light of day away in front, till it suddenly came out into a clearing full of sunshine; presently, as if it were retracing its road, it rushed into another burrow, and emerged with the strident yell of a steam whistle and deafening clatter of wheels, to fly up the winding ribbon of road cut in the living rock.

Suddenly the peaks parted, a wide opening brought the train out into broad daylight; the scene lay clear before them, terrible on all sides.

“Le Drac!” (the river) exclaimed the Abbé Gévresin, pointing to a sort of liquid serpent at the bottom of the precipice, writhing and tossing between rocks in the very jaws of the pit.

For now and again the reptile flung itself up on points of stone that rent it as it passed; the waters changed as though poisoned by these fangs; they lost their steely hue, and whitened with foam like a bran bath; then the Drac hurried on faster, faster, flinging itself into the shadowy gorge; lingered again on gravelly reaches, wallowing in the sun; presently it gathered up its scattered rivulets and went on its way…the rippling rings spread and vanished, skinned and leaving behind them on the banks a white granulated cuticle of pebbles, a hide of dry sand.

Durtal, as he leaned out of the carriage window, looked straight down into the gulf; on this narrow way with only one line of rails, the train on one side was close to the towering hewn rock, and on the other was the void. Great God! if it should run off the rails! “What a crash!” thought he.

And what was not less overwhelming than the appalling depth of the abyss was, as he looked up, the sight of the furious, frenzied assault of the peaks. Thus, in that carriage, he was literally between the earth and sky…along interminable balconies without parapets; and below, the cliffs dropped avalanche-like, fell straight, bare, without a patch of vegetation…all round lay a wide amphitheater of endless mountains, hiding the heavens, piled one above another, barring the way to the travelling clouds, stopping the onward march of the sky…

The landscape was ominous; the sight of it was strangely discomfiting; perhaps because it impugned the sense of the infinite that lurks within us. The firmament was no more than a detail, cast aside like needless rubbish on the desert peaks of the hills. The abyss was the all-important fact; it made the sky look small and trivial, substituting the magnificence of its depths for the grandeur of eternal space.

The Abbé had said that the Drac was one of the most formidable torrents in France; at the moment it was dormant, almost dry; but when the season of snows and storms comes it wakes up and flashes like a tide of silver, hisses and tosses, foams and leaps, and can in an instant swallow up villages and dams.

“It is hideous,” thought Durtal. “That bilious flood must carry fevers with it; it is accursed and rotten…Durtal now thought over all these details; as he closed his eyes he could see the Drac and La Salette.

Chartres

La Drac 1900

Recent Comments