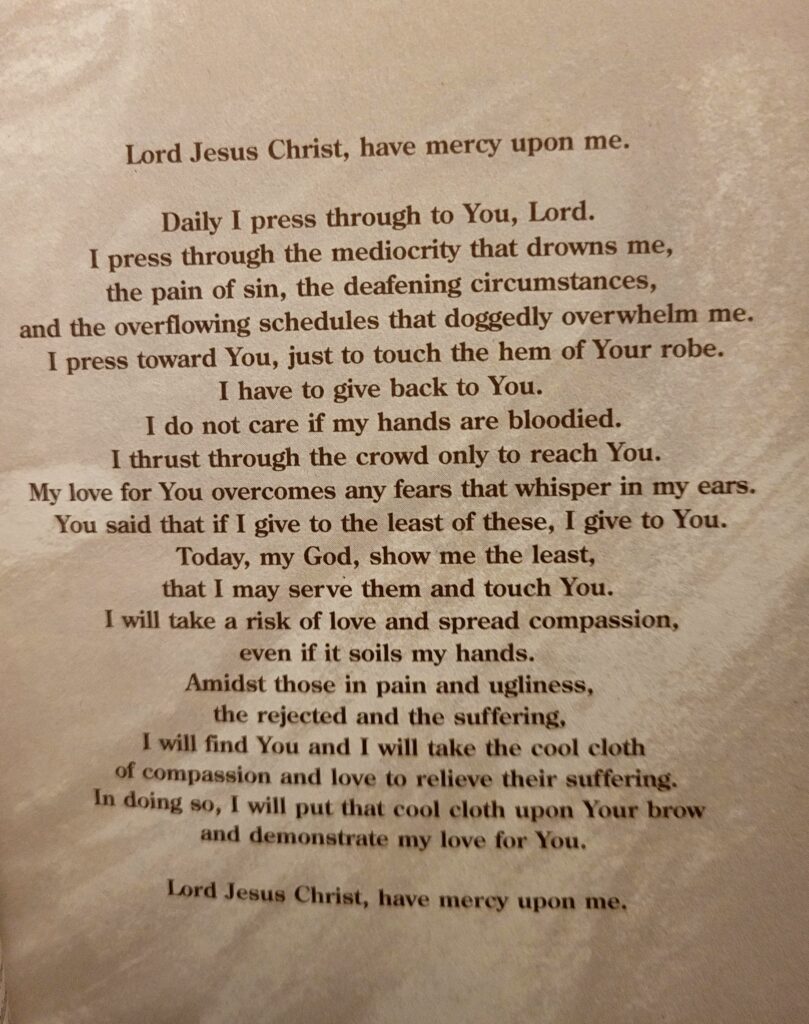

In later spiritual theology, the word “ligature” recently mentioned became useful for describing the binding or tightening effect on the faculties in their incapacity to exercise themselves in discursive meditation or to find satisfaction in it. This tying down of the faculties extends into the early period of contemplation. Everything now in prayer becomes at times very dim and imperceptible to the soul. Grace is at work in drawing the soul to the deeper quiet where God hides his presence in the inner recesses and caverns of the soul. But for the moment, the soul is unable to appreciate what is happening. It is conscious more of the tightness it feels and the inability to move freely in any internal activity. The inclination gently stirring within the soul from infused grace is not so noticeable. What our soul does know, if it is attentive to its inner inclination, is a desire to be alone with God in silence, which compensates for the tightening of the faculties and their incapacity: “Ordinarily this contemplation, which is secret and hidden from the very one who receives it, imparts to the soul, together with the dryness and emptiness it produces in the senses, an inclination to remain alone and in quietude” (DN 1.9.6). And yet it is often the case that souls do not surrender to this inclination to remain quietly alone with God. The reason is usually the confused state of the experience in the early period of contemplation. The following passage from The Dark Night insists on the importance, in effect, of an exercise of spiritual intelligence in allowing God to do his work of sanctification in this new experience of contemplation. Receptive surrender to God is always the key disposition that a soul should cultivate in contemplation.

“And even though more scruples come to the fore concerning the loss of time and the advantages of doing something else, since it cannot do anything or think of anything in prayer, the soul should endure them peacefully, as though going to prayer means remaining in ease and freedom of spirit. If individuals were to desire to do something themselves with their interior faculties, they would hinder and lose the goods that God engraves on their souls through that peace and idleness. If a model for the painting or retouching of a portrait should move because of a desire to do something, the artist would be unable to finish and the work would be spoiled. Similarly, any operation, affection, or thought a soul might cling to when it wants to abide in interior peace and idleness would cause distraction and disquietude, and make it feel sensory dryness and emptiness. The more a person seeks some support in knowledge and affection the more the soul will feel the lack of these, for this support cannot be supplied through these sensory means.” (Dark Night of the Soul)

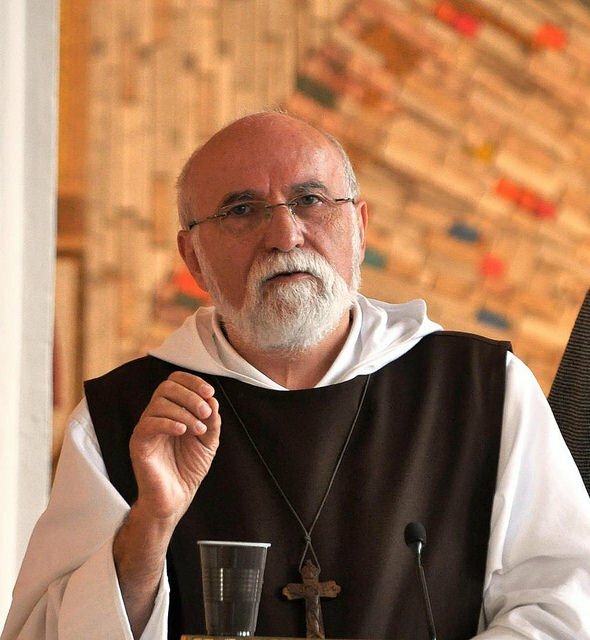

“Saint John of the Cross: Master of Contemplation” written by Father Donald Haggerty

Recent Comments