It has been well over six months since I last posted. I am ending a two-month sabbatical, a summer time of healing that found me in Indianapolis for thirty days, and then onto the guidance of a recovery center in Royal Oak, Michigan. Most recently, I am coming off a weekend at the Eucharist Congress of 2024 in Indianapolis—a reinvigorating time deepening Catholic commitments and devotions. An emerging conviction, and thorough effort, is being invested in my formation as a teacher of English Literature. The time away from worldly concerns, and assumptions, deepened my passions, while assisting in identifying strengths which will allow me to live a healthy life. Self-destructive ways have their roots which guilt and shame will not alleviate. My God given talents and interests will be unleashed. Self-reliance, trust, and confidence will be recognized as assets. Diligence, fortitude, and a strong work ethic are called forth.

During the 30-day Indianapolis retreat, I devoured English, and one Irish, Gothic novels, while holding to a Catholic spiritual path with the reading of Father Donald Haggerty’s ‘Saint John of the Cross’. Many influences were explored in Indianapolis. A quote from the saint’s ‘Ascent of Mount Carmel’: “The heart of the fool, states the Wise Man, is where there is gladness; but the heart of the wise is where there is sadness.” I would like to examine the consumed Gothic novels.

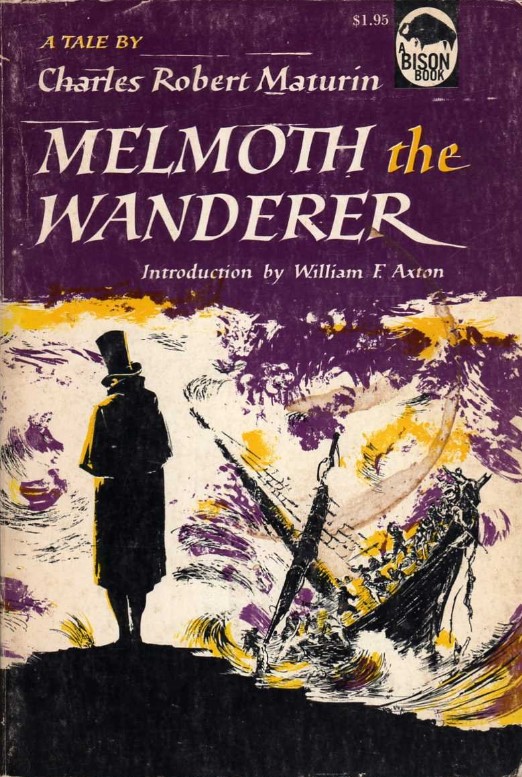

First a difficult and long read, yet amazing in moments of terror and depth of character exploration. ‘Melmoth the Wanderer’ by Charles Robert Maturin captivated as I slowly moved through it. It called forth the deep dive into Gothic novels. Stories and tales nested within one another, ‘Melmoth the Wanderer’, intensely delves through massive depths of despair and darkness as the inheriting nephew of misfortune attempts to untangle the overarching complications caused by his ancestor’s evil alliance. Melmoth haunts the novel detailing the fate of others. One of the others is the Spanish survivor of the witnessed shipwrecked, Alonzo Moncada. The Spaniard tells of his foiled escape from the monastery his family imprisoned him with the assistance of his brother who will futilely lose his life in the desperate deed. The nature of the ferocity of Maturin’s storytelling is apparent in a quote in which Alonzo and his brother endure through the trials of their shared failure. The quote is a moment in which the struggling brothers are granted a false sense of victory.

“Yet I was now on the verge of liberty, and though drenched, famishing, and comfortless, was, in any rational estimate, an object much more enviable than in the heart-withering safety of my cell. Alas! It is too true that our souls always contract themselves on the approach of a blessing, and seem as if their powers, exhausted in the effort to obtain it, had no longer energy to embrace the object. Thus we are always completed to substitute the pleasure of the pursuit for that of the attainment,–to reverse the means for the end, or confound them, in order to extract any enjoyment from either, and at last fruition becomes only another name for lassitude.”

Lassitude being a condition of weariness or debility, a condition I found enwrapping me in Indianapolis. Age accumulating, I feel the time of my years weighing down, yet nowhere near being defeated by them. A sense of urgency arises which calls forth further the pursuit. The next Gothic novel was Mary Shelly’s ‘Frankenstein’, the fantastical unrealistic science fiction novel of a manmade man contemplating the nature of existence. His obsession with his irresponsible creator devours his mind and actions after a failed attempt to lovingly, compassionately, and caringly integrated himself with his fellow living beings through a family escaping worldly complications as they secrete themselves within the beauty of nature provided by a mountainous hideout. The hideous monster fails miserably in his effort of social integration. Due to his physical deformities, the family recoils abhorrently upon his carefully planned out introduction. First, he presented himself to the blind father, able to hide his ugliness until the children appeared. True in intent, honorable in heart, I found his alienated reasoning impressive: “I admired virtue and good feelings and loved the gentle manners and amiable qualities of my cottagers, but I was shut out from intercourse with them, except through means which I obtained by stealth, when I was unseen and unknown, and which rather increased the satisfied the desire I had of becoming one among my fellows.”

The next Gothic novel was the most bizarre. Matthew Lewis’ sensational and bonkers novel ‘The Monk’ took the Gothic genre immensely into the supernatural and realm of extraordinary events. I recognized a common theme within the Gothic novel genre. Typically, Gothic stories are set in exotic foreign countries of Catholic devotion, usually Spain or Italy the culprit. Superstitious Old-World settings of corrupt religious practices play themselves out in mammoth aged monasteries or castles. The colossal structures of times-since-past are inhabited with secret passages, hidden rooms, underground lairs, ghosts, creaking sounds and unfathomable depths of decadence and corruption. Darkness and mystery lurk behind locked and hidden doors. In mindset, a not-so-subtle protestant and puritan assault upon Catholicism pervades the English and Irish Gothic novels.

‘The Monk’ possesses an astonishing complicated plot of several stories concurrently swelling into a romantic happy ending; however, pleasantries are overshadowed by the perversity and degradation of the atrocious relationship between the prideful abbot Ambrosio—the story intimately detailing his obsessive decline and frustrating descent into mortal sin and ultimate self-chosen damnation—with his deranged occultist inferior brother, Rosario, who turns out to be a sister, and the demoralized ways of the austere and ruthless Poor Clares. The extremes of the depravation inflict the story with an absurdity that negates serious critique. Maturin is ignorantly errant of the monastic life he attempts to dissect as corrupt. His fictious monastic order is a Franciscan order. In truth, Franciscans did not exercise cloistered monastic lives, instead involving themselves in the world as mendicants. St Francis had his time of hermitage, as all Franciscans do, yet the Franciscan charism is one of tending to and giving back to the world, an immersion in the mud with their brothers and sisters. Lewis’ impressive literary skills, including his writing of poetry filling the novel, give credence to the worthiness of a read, yet in other regards it can easily be dismissed as imprudence. Though Lewis intends to credit many of Ambrosio’s faults to the monastic life, I did feel his defining of a corrupt spiritual life of one devoted to the pursuit of faith to be worthy of consideration.

“His instructors carefully repressed those virtues whose grandeur and disinterestedness were ill-suited for the Cloister. Instead of universal benevolence, He adopted a selfish partiality for his own particular establishment: He was taught to consider compassion for the errors of Others as a crime of the blackest dye: The noble frankness of his temper was exchanged for servile humility; and in order to break his natural spirit, the Monks terrified his young mind by placing before him all the horrors with which Superstition could furnish them: They painted to him the torments of the Damned in colors the most dark, terrible, and fantastic, and threatened him at the slightest fault with eternal perdition. No wonder that his imagination constantly dwelling upon these fearful objects should have rendered his character timid and apprehensive. Add to this, that his long absence from the great world, and total unacquaintance with the common dangers of life, made him form of them an idea far more dismal than the reality. While the monks were busied in rooting out his virtues and narrowing his sentiments, they allowed every vice which had fallen to his share to arrive at full perfection. He was suffered to be proud, vain, ambitious, and disdainful; He was jealous of his Equals, and despised all merit but his own: He was implacable when offended, and cruel in his revenge.” Quite a wretched and irrational portrayal Lewis ascribes to one who rises up through the ranks of a monastery, yet not without a certain merit for consideration.

The next English Gothic novel was ‘The Castle of Otranto’ by Horace Walpole, another tale set in the superstitious Old World of Catholicism: Italy and a castle riddled with secret passages, a prophecy of doom pervading, a corrupt obsessive king abusing power, and a hero emerging into an identity to righteously claim his throne.

“The beholders fell prostrate on their faces, acknowledging the divine will. The first that broke silence was Hippolita. My lord, said she to the desponding Manfred, behold the vanity of human greatness! Conrad is gone! Matilda is no more! In Theodore we view the true prince of Otranto. By what miracle he is so, I know not—suffice it to us, our doom is pronounced! Shall we not, can we but dedicate the few deplorable hours we have to live, in deprecating the farther wrath of heaven? Heaven ejects us—whither can we fly, but to you holy cells that yet offer us retreat?—Thou guiltless but unhappy woman! Unhappy by my crimes! Replied Manfred, my heart at last is open to thy devout admonitions. Oh! Could—but it cannot be—ye are lost in wonder—let me at last do justice upon myself! To heap shame upon my own head is all the satisfaction I have left to offer to offended heaven. My story has drawn down these judgements: let my confusion atone—But ah! What can atone for usurpation and a murdered child? A child murdered in a consecrated place?—List, sirs, and may this bloody record be a warning to future tyrants.”

Anne Radcliffe’s ‘The Italian’ stepped the Gothic novel genre into a new realm of romantic literary excellence. The magnificence of her graceful writing: vocabulary, sentence structure, character development, and storytelling soothed with a preciseness and purpose. Like Louisa May Alcott, Radcliffe was a writer who enjoyed immense success during her lifetime, able to earn substantial income. Something few could achieve through writing. Yet she remained a publicly elusive woman, hiding in the privacy of her homelife. She never ventured away from her home during her time of writing. A product of English Protestantism, her childhood was immersed in the culture of Unitarian Dissent. Depth to her personal beliefs is never defined. The darkness of her tales opposed upbringing and contemporary standards. There were long periods of non-writing, as well as a lack of self-diagnosed literary commentary. Though successful, no one knew exactly what she was up to. Criticized as an enchantress of terror, there is the idea she was highly sensitive to her critics, while others identify her husband’s puritanical disapproval of her perceived macabre stories. There would be no explanations to her lengthy novels. Her husband would burn her unpublished writing after her death. The woman of tremendous influence remains aloof.

I found her imagination and care with her characters to be inspiring. Her contemplative ability to course her writing into a descriptive immersion into the beauty of nature proves to be a splendid spiritual excursion—a Transcendental endeavor. Ellena imprisoned in the monastery of San Stefano, amidst the horror of her human condition while victim to infallible institutional powers, discovers access to a terrace overlooking the mountains. Horribly grief stricken, she can sit ahigh and contemplate the wonders of creation. The marvel suffices against her wretched woes—alleviating yet not resolving. Her natural state of awareness is provided a means of expression. Nature not only abounds, it sustains and breathes truth beyond human understanding and condition.

“Hither she could come, and her soul, refreshed by the views it afforded, would acquire strength to bear her, with equanimity, thro’ the persecutions that might await her. Here gazing upon the stupendous imagery around her, looking, as it were, beyond the awful veil which obscures the features of the Deity, and conceals Him from the eyes of his creatures, dwelling with a present God in the midst of his sublime works; with a mind thus elevated, how insignificant would appear to her the transactions, and the sufferings of this world! How poor the boasted power of man, when the fall of a single cliff from these mountains would with ease destroy thousands of his race assembled on the plains below! How would it avail them, that they were accoutered for battle, armed with all the instruments of destruction that human invention ever fashioned? Thus man, the giant who now held her in captivity, would shrink to the diminutiveness of a fairy; and she would experience, that his utmost force was unable to enchain her soul, or compel her to fear him, while he was destitute of virtue.”

The final Indianapolis novel, Jane Austin’s ‘Northanger Abbey’, though not truly a Gothic novel, highlights the fascination of nineteenth century readers with Gothic novels. The main character, Catherine Morland, is obsessed with Gothic novels, especially Radcliffe’s ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho’. Catherine asserts that her experience of Gothic novels will be “…all story and no reflection”, yet in this coming-of-age tale it is interesting to see the effects dark stories have upon her imagination and perception of others. All ends well as Catherine sticks to her principles while holding no resentments after being unjustly evicted from the home of the Tilney family she came to love. Her good manners are rewarded with a proposal from Henry, the Tilney’s son.

Recent Comments