A Carthusian

A poet’s limited vision

Wandering between two worlds, one dead,

The powerless to be born,

With nowhere yet to rest my head,

Like these, on earth I wait forlorn,

Their faith, my tears, the world derides—

I come to shed them at their side.

To keep himself (the poet Matthew Arnold) in countenance, he has to regard the Carthusians too as ghosts, unmanned men, half realities flitting between sheer nothingness and full-bodied life; they are, like himself, survivors—he, “last of the race of them who grieve”; they, last “of the people who believe.”

He has to set them besides himself, looking regretfully out at the life of action—he, spoilt for it by his corroding agnosticism, which is yet to find any satisfaction in any hard and gay materialism; they, because they can’t help themselves either: their “bent was taken long ago”; action and pleasure call them “too late”; they beg not to be disturbed, but to be left in reverie, shade, and desert peace.

Well, we must allow Matthew Arnold had to be melancholy, but really we can’t have him suggesting Carthusians are. It is perfectly true that ex-soldiers, ex-judges, ex-courtiers, ex-roues (a debauched man, especially an elderly one), are to be found in plenty within these cloisters; it is true, too, that they would say, looking back upon their old lives, it was, in a sense, “the vanity” which the ancient writer called it; but they wouldn’t allow that they had, by old experience or new self-oblation, lost anything. The gaiety of novitiates is proverbial, and the stricter the gayer,,,a weight has indeed been removed, it leaves a man freer and stronger to march, and gives him reasonable hopes of attaining. Really it is time that the old myth of cloisters filled with disillusioned men and jilted girls be given up. Postulants don’t go there out of pique, or to hide, or to pine, or to look backwards generally; but in the certainty of finding the positive, the substantial and the stimulating. Nor are they packed with cheated boys, “cooked vocations,” anemia and ignorant lads destined afterwards to look wistfully across the grilles at banners and bugles, pomp and pleasures, too little appreciated to cause more than the mildest stirring of their atrophied instincts. Carthusians do not, I dare say, laugh much, but I know they can smile, and very humoursly; and I fear they would be outright tempted to chaff the plaintive poet who came to beg permission to mingle his tears with theirs; the poet, lamenting that he had been forced to abandon much, and had got nothing in return; deploring even the high sacrifice and sorrows of others—a Byron’s, a Shelly’s, a Senancour’s, since no one was a bit the better for their effort and their pains….Sacrifice and sorrow are indeed, the Carthusians’ motto would confess, a world-abiding law, but they are quite sure they possess a life, so expansive and transcendent and unitive that there is no room for repining. The Cross stretches arms wide to embrace the universe; the agnostic frets and dwindles within the circle of himself. Stevenson, temperamentally very different than Matthew Arnold, yet sees the monks from somewhat the same angle. Frankly they are skulkers. He, with all the spirit of life pulsating in his brain, passes too “out of the sun,” out of reach of lute and fife, rumor of the world at large, and holier realm of “confidences low and dear.” There, at “Our Lady of the Sorrows,” he finds the “unfraternal brothers,” “aloof, unhelpful and unkind, the prisoners of the iron mind”—

Poor passionate men, still clothed afresh

With agonizing folds of flesh;

Whom the clear eyes solicit still

To some bold output of the will.

Fancy and Memory conspire to call them, and him, “to heroic death,” or to “uncertain fresh delight.” To the “uproar and the press,” to “human business,” to laughter, honor, fight and failure and new flight, he summons them from their “prudent turret and redoubt.” God, spying from Heaven’s a top “the noble wars“ of mankind, shall like enough “pass their corner by”—

For still the Lord is Lord of might,

In deeds, in deeds, He takes delight.

The plough, spear, ship, city; the streets, the fields; the climber, the songster; the unfrowning “Caryatides” (a stone carving of a draped female figure, used as a pillar to support the entablature of a Greek or Greek-style building) who by their “daily virtues,” weaken enough, no doubt, yet “under-prop” high Heaven; trade, marriage, motherhood; the sowers of gladness—these He will approve.

But ye! O ye who linger still

Here in your fortress on the hill

With placid face, with tranquil breath,

The unsought volunteers of death,

Our cheerful General on high

With careless looks may pass you by.

–C.C. Martindale ‘Upon God’s Holy Hills: The Guides St. Anthony Of Egypt, St. Bruno of Cologne, St. John Of The Cross’

St Bruno: Carthusian founder

Perhaps there can be nothing more impressive than the spectacle of that inner, personal life by which a man is living. All men have it. Beneath the plate-armor of bluff, behind which even the most frivolous-seeming hide from their own eyes and the world’s, what loneliness, what melancholies, what disgusts! And in the futile and degraded, the hopelessly unsuccessful in morals, in human intercourse, in lovableness, what secret efforts and hopes, what tentative affections! And in the hard and brilliant, what secret efforts and hopes, what self-distrusts, what giddiness, as abysses yawn suddenly at their feet! Shall we say that in proportion as we get really close to the world’s nondescripts, the weaklings, we are approaching a vision of encouragement, even awe? And as we near the soul of the successful, the popular, and the four-square monarch of a man, we are preparing for ourselves an all but heartbreak of anxious pity?

But what puts us on our knees is the sight of a strong interior life within, and alien to, a strong-outside activity; when, in a Bruno, successful as professor, and hard fighter in the world of men, affairs and money, is revealed a soul aloof from all these things, wanting all the while, something quite different,–in tone, not with the crabbed dialectic of the classroom, nor with the fretful noises of courts and councils, but with the mountains, the firwoods, and the frozen stars of winter, This, not, as I said, through weakness, but through a width and depth of vision and a force of will, unable, quite, to submit to all these tyrannies. –C.C. Martindale ‘Upon God’s Holy Hill: The Guides of St Anthony of Egypt, St Bruno of Cologne, St John of the Cross’

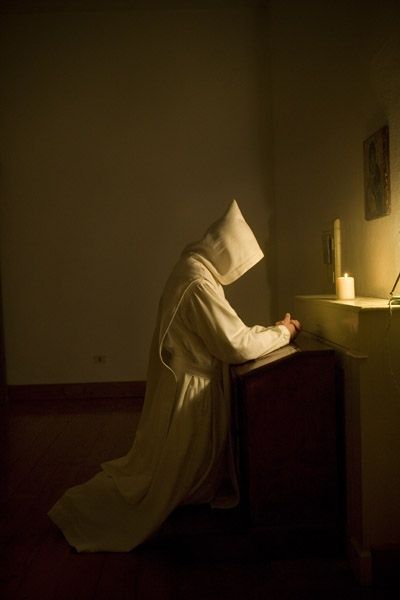

Walking the walk

At my evening examination of conscience I go through the past day peacefully, checking to see if I was neglectful and have left God in my soul unnoticed for too long a time. In doing so, I discover that I was most troubled with mistakes when my neglect of God was most prolonged. While grace perfects its work in us, let us help it along as much as we can. We strive with human means to bring an intense interior life to fulfillment and further development. Thus, for example we seek through reading and study to penetrate more deeply into the truths of holy Church, especially its lofty teaching about the divine filiation of souls called to participate in divine life.

Above all else, I shall make use of the most excellent means, the holy sacraments. I shall l receive them as often as possible and with the greatest possible love and self- surrender. For the humanity of our Savior is the gateway to his divinity. No one comes to God the Father except through Jesus his Son.

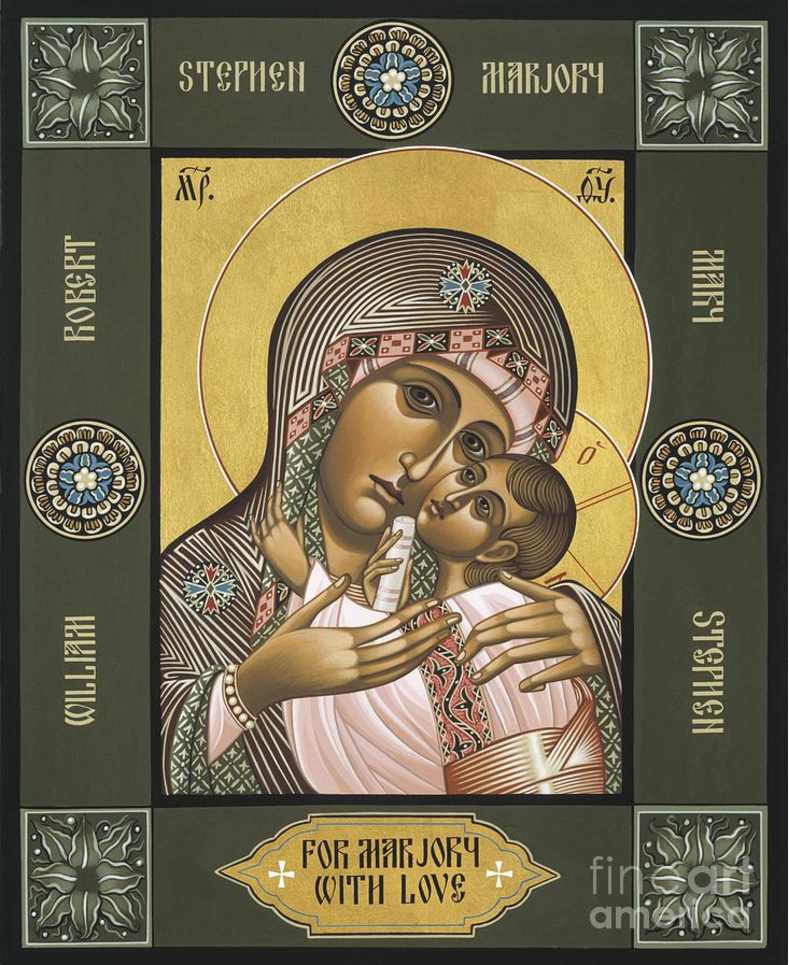

In a mysterious way, Jesus purifies us from our sins and failures in holy absolution. In the Holy Eucharist he approaches us with his humanity and leads us ever deeper into his divinity. And when the sacramental species are no longer present in us, we can continue our communion, our union with the divinity of our Redeemer, until the next sacramental bonding. Our thanksgiving does not limit itself to a few minutes. With the disciples of Emmaus, we ask our divine Savior after Holy Communion: “Lord, stay with us!” (Lk ’24:29). Thus it becomes the unsurpassable source of our inner life: its efficacy expands to our whole day and fills us with ever new zeal. Let us raise our eyes filled with trust to the loving Mother of God, who is also our mother. She has given us the life of the Redeemer and she will also lead us to supernatural life, until, having grown to maturity in her son Jesus, we reach the perfection of unity with him.

Mary, mother of fairest love, lead us to Jesus! A. Carthusian ‘Life in God’s Presence’

MARY, MOTHER OF FAIREST LOVE painted by Father William Hart McNichols

“…Strike that thick cloud of unknowing with the sharp arrow of longing love, and on no account whatever think of giving up.” Cloud of Unknowing as quoted by Father McNichols In the Life of the Blessed Virgin (taken out of the 4 volumes of the life of Christ ) there is the true sign given to Elijah in 1 Kings 18 : 44 of one single cloud appearing in the sky, which ends a terrible drought. Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich sees the cloud as symbolic of the Blessed Mother herself ; Mary’s entrance into our world ends the drought of waiting for the Messiah.

Every day a new day

What up until now seemed to me like obstacles, such as temptations, distractions, internal and external difficulties, will now serve as helps to me. When earlier, instead of rising, I always fell deeper through my sins, faults, and weaknesses, I just stayed there. I did not know how to make use of my failings. Now, however, I see that with the grace of God that “fall” can be used to raise me so much more surely to God, and bring me to my goal…what might previously have been a hindrance and source of discouragement to my efforts can now serve as the means for raising me up from creatures to their Creator. In all of this I now recognize a pressing invitation of God to unite myself as closely as possible with him through acts of faith, trust, selfgiving, and love. And so everything discouraging is for me a pure grace, which enables and invites me to live more and act more through God and in God.

Haste, fearful self-consciousness, and distraction have till now so often influenced and ruled my life. From now on, however, I shall live with a spirit of trust and of pure abandonment to God’s all-knowing and all gracious providence. Before, nothing so depressed and worried me as my failings and weaknesses, but now I boast of them in the spirit of contrition. “I will all the more gladly boast of my weaknesses, that the power of Christ may rest upon me” (2 Cor 12:9). They should help to convince me of the nothingness of my own ego and move me to let myself be completely filled by Christ, insofar as through the awakening of faith, confidence, and love I unite myself more and more intimately with God. The feelings and desires of the old man must die out. “He must increase, but I must decrease—Illum oportet crescere, me autem minui” (Jn 3:30). The more I recede, the more will he grow.

So little by little I will overcome the unforeseen occurrences of life and the petty things of this world and master them. All of my former enemies are now helpful to me in moving me closer to my ideal, and they serve to push me towards ever greater faithfulness and generosity and to trust that is ever more intimate –A. Carthusian ‘Life in God’s Presence’

Carthusian celebration

Now I have found the ideal of my hoping and striving, bursting with energy, shining with dedication, saturated with the blood of sacrifice. Now I know what I want to, can, and should attain. Up until now I lived without a clear-cut goal, and the discomforts of the way made me tired and discouraged. Now, however, I see clearly, I am sure of my way and my goal, and nothing should hold me back from now on. I will not rest until I have found God in the innermost region of my heart. “I found him whom my soul loves. I held him, and would not let him go” (Song 34). Love lends me wings, “for love is strong as death” (Song 8:6). I will no longer shrink back from difficulties, for “I can do all things in him who strengthens me” (Phil 4:13).

When I look over my past life, I must admit that I have made such little prowess in the spiritual life because I was lacking in the proper goal.

I didn’t understand how greatly our divine Savior was thirsting for souls who would give themselves to him without reserve and to whom he could give himself with the same fullness. The degree of our trust and unity with him is by the extent of the generosity with which we follow the invitations of grace. Jesus did not set any limits to his love. He only longs to give himself wholly and to be able to possess souls without any reservations. But souls fear him, since they shy away from the requirements that this intimacy demands of men and women: sacrifice and self-denial.

From now on I shall be honest and upright with myself. I know that God wants to take complete possession of me and that he has predestined me to be transformed into the image of his Son Jesus. He wants me to be his child despite my unworthiness. Who can consider themselves worthy of such favor?

But it is not “in spite of’ my unworthiness that God longs for my soul. Rather it is precisely because of my misery that he wants to make me a masterpiece of his love, mercy, and glorification. The more unsuitable the material is, the greater the fame and prowess of the artist, who succeeds despite everything in making a work of art out of it. Our divine Savior wants to bring this truth to us more clearly and help us to grasp it through the parables of the prodigal son and the lost sheep. For there is more joy in heaven over a single converted sinner than over the perseverance of a whole multitude of the just.

Since I have resolved, from now on, to strive for this ideal, I must recognize in all of my thinking, willing, and doing that I am nothing of myself, so that I can give myself over to him with my whole being and all that I have.

The important thing is to believe effectively in his love. “Your faith has made you well” (Lk 8:48).–A. Carthusian ‘Life in God’s Presence’

A. Carthusian ‘Life in God’s Presence’

God would not be the eternal goodness and wisdom if he did not—along with his courting of our love— give us the means to this unity with him. These means, which bring us with certainty into direct relationship with God, are the three theological virtues and the gifts of the Holy Spirit that accompany them.

By faith we affirm the truth of the divine life that has been promised to us. Through love we possess it. Hope gives us the certainty that with the help of grace we will grow in this life and finally possess it perfectly and unendingly in heaven. In this activity of the three theological virtues is the substance of every deep and sincere prayer. We can carry on a conversation directly with God in the innocence and simplicity of our souls. “In simplicitate cordis quaerite illum—Seek him with simplicity of heart” (Wis 1:1).

………

The work of the imagination is a purely human activity, and therefore it is not prayer. That’s the first reason why we want to reduce it to what is essential. Of course, through the influence of grace this subordinate activity is ennobled and can be directed toward a supernatural goal. But despite this, it is still true that the power of the imagination, like any capacity related to sensation tires quickly and grows weary of its object. To call forth fantasy pictures and hold on to them is too strenuous a task for one to be able to continue with for any length of time. Consequently, we can’t obtain any substantial or even notable part of our prayer life from this source since, according to the demands of the Gospel, prayer should be simple and continual. “Oportet semper orare et non deficere—One ought always to pray and not lose heart” (Lk 18:1).

Besides, the imagination is not able to get in touch with the supernatural realities. These are only accessible through pure faith. One can at most play with the shadows, the veils of these invisible realities, while we can reach immediate, interior connection with them through the divine virtues. –A. Carthusian ‘Life in God’s Presence’

A link to an insightful review of Scorsese’s film ‘Silence by a Dominican brother.

Recent Comments