The soul is not plunging into a state of quietistic oblivion. It is not disappearing into an inward state of nothingness, with a loss of identity and all awareness. The passivity stressed by Saint John of the Cross has to do with the withdrawal from any active pursuit of a knowledge or an experience. The passivity is in the refusal to direct or control what is taking place. The soul allows God to take the lead. On the other hand, there is a certain active receptivity necessary in such prayer, at least in its beginnings. Our soul must accept the inclination that it delicately experiences of being drawn to an inner “cavern” of loving quiet where a desire for God is present deeply within it. The effort, mildly and gently undertaken, is to remain open, receptive, free to being drawn, but refusing as well to grasp at an experience or at any kind of knowledge. As Saint John of the Cross just affirmed in the last passage, one is not entirely passive in keeping one’s eyes open to receive light. The surrender to that light occurs passively but cannot take place except that

our soul is willing to be receptive and does not obstruct this receptive disposition. The result is a knowledge bestowed on the soul by a love to which it surrenders itself. As Saint John of the Cross writes: “This reception of the light infused supernaturally into the soul is passive knowing. It is affirmed that these individuals do nothing, not because they fail to understand but because they understand with no effort other than receiving what is bestowed. This is what happens when God bestows illuminations and inspirations, although here the person freely receives this general obscure knowledge” (AMC 2.15.2).

It is important also to reaffirm that the inclination to remain alone and quiet with God, in a peaceful desire and loving awareness, without making acts or pursuing discursive exercises, must be a real state of grace granted to a soul. The danger in the realm of deeper prayer is to seek possessively after a “state of prayer” that is not being given by grace. There are people who might choose by way of preference to cultivate a state of “induced quietude” in prayer. The practice, for instance, of slowly repeating a single word or a mantra, as so-called “centering prayer” teaches, can be an example of this. The method may bring a “quietude” to the psyche, emptying thoughts from the mind and conveying a noticeable tranquility to the inner feelings. But these effects have their likely source in the rhythmic repetition of the mantra. It is a serious misrepresentation to identify this practice and its effects with genuine contemplative prayer. The symptoms induced by the method are quite capable of coexisting with an indifference in some lives to grave personal immorality. That in itself should raise questions. No method of prayer advertised as a contemplative practice of prayer can dispense with the need to pursue virtuous and sacrificial living. Even for a person in a state of grace, however, the inward quiet and tranquilizing peace experienced in pseudo-contemplative approaches pose a dubious and deluding feature. These effects are generally sought as a goal in themselves as part of a self-oriented pursuit, rather than coming as an inclination moved by a grace drawing the soul to God. In that case, the real focus is not directed toward God. And the passivity of inner emptiness, with the mind doing nothing, becomes over time a harmful condition for a soul. The person would not be turning with loving attentiveness to God, but descending into a progressive exercise in self-absorption. The fruits, as always, are seen in time. Without addressing, of course, contemporary practices, Saint John of the Cross is nonetheless clear on the importance of a careful discernment.

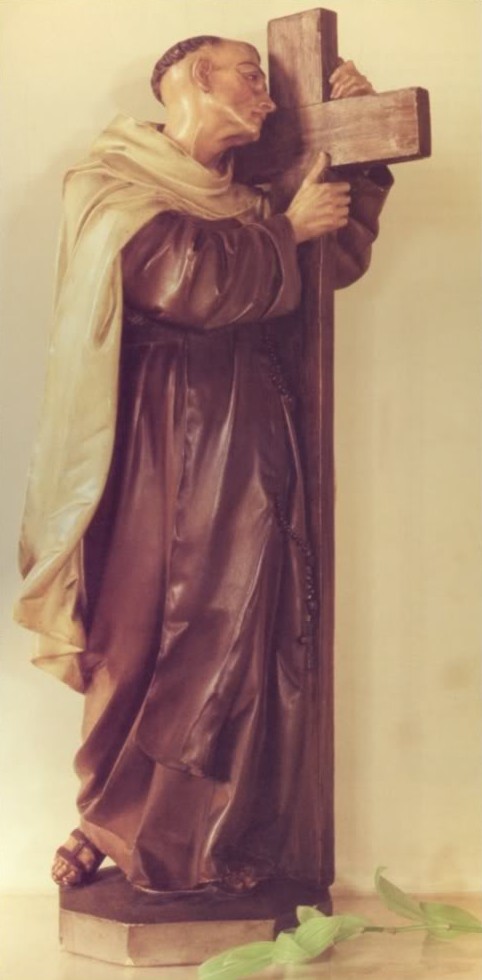

St John of the Cross: Master of Contemplation written by Father Donald Haggerty

Recent Comments