He (J.K. Huysmans) had spent much of his leisure at Ligugé working on his projected Life of St. Lydwine of Schiedam. The subject had long been in his mind, for she was one of his favourite saints, and even before his conversion he had been collecting materials. He had turned the pages of Gerlac, Brugman and À Kempis. He had come across a nineteenth-century hymn, preserved by the Bollandists, formerly sung in honour of Lydwine in Holland and Belgium:

Mira patientia

Vixit in hoc tempore,

Nimiæ miseria

Particeps in corpore.

Non murmur resonat,

Non querimonia,

Sed laudem personat

Devota Lydia.

He had even found in a Jansenist breviary of the eighteenth century an Office Propre de la Bienheureuse Lidwine. It was not until 1892 that an Office de Sainte Lidwine was conceded to the churches of Holland by a decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites.

His taste always had a bias towards the bizarre, not to say the macabre. He was chiefly interested in saints whose lives had something extraordinary about them, something extra-vagant, the victims of suffering almost beyond human imagination: St. Lydwine, St. Colette, St. Françoise Romaine, the Blessed Jeanne de Maillé: living effigies of the Passion and bearing its marks in their own flesh. He liked his saints to be sick and was fond of repeating the remark of St. Hildegard that ‘God does not inhabit healthy bodies’. On this count at least St. Lydwine was the perfect subject, for she is said to have suffered from every disease known to the Middle Ages except leprosy. She was also particularly dear to Huysmans as a native of those Low Countries for which he had always an atavistic tenderness.

Lydwine was born at Schiedam in the closing years of the fourteenth century. She was very beautiful but lost her good looks through illness at the age of fourteen. Shortly afterwards she fell, while skating on the frozen canals, broke a rib, and for the rest of her life was bed-ridden. The most horrible ills assailed her, her wounds festered and worms bred in her putrefying flesh. Her right arm was eaten away with erysipelas so that only a single muscle held it to her body, her forehead was a gaping scar, she became blind in one eye and with the other could only bear the dimmest of light.

Then the plague ravaged Schiedam, and she was the first victim. Two boils formed on her body, one under her arm, the other over the heart. ‘Two boils, it is well’ she said to the Lord, ‘but three would be better in honour of the Holy Trinity.’ Immediately a third boil broke out on her face. She still thought herself too fortunate and entreated God to allow her to expiate, by her sufferings, the sins of others. Her prayer was answered, and for thirty-five years she endured every imaginable ill, taking no food but the Eucharist, and living in a cellar, fetid in summer and so cold in winter that

her tears were frozen on her cheeks.

But the Lord rewarded her with visions of His glory, sent angels to minister to her and communicated her with His own hand. Her festering sores exhaled delicious perfumes, and when she died her former beauty was miraculously restored to her. Crowds came to see her and all who were sick were healed.

Such was the story which Huysmans set himself to tell in terms of the Naturalism he had learned from Zola; and the result is enough to turn the strongest stomach. And yet the conscientious reader is compelled to admit that the method, in the end, succeeds. For Lydwine becomes, unlike most of the subjects of the hagiographers, a real person. The reader is compelled to accept her as he accepts a character in a realistic novel, to regard her, as Huysmans did, with a growing tenderness, to take part in her sufferings, to share her faith.

The doctrine of mystical substitution fascinated Huysmans as we can see by the conversation which he puts into the mouths of Durtal and the Abbé Gévresin in the early pages of En Route. He calls it ‘that miracle of perfect charity, that superhuman triumph of Mysticism’, and he made it, as he had always intended to do, the central theme of his Life of St. Lydwine. But perhaps he could never have written of it with so much conviction if he had not now begun to suffer the physical agonies which were to be with him, in ever increasing measure, until the day of his death. An author must always, to some extent, identify himself with his principal character, but to have the right to identify himself with St. Lydwine, Huysmans must himself suffer. While he was still unconverted he had complained of neuralgia; when he was at Ligugé he had to make several visits to Poitiers in order, as he imagined, to have his teeth attended to. Now that he had returned to Paris the pain had grown worse, and whether he knew it or not, what he was suffering from was cancer of the mouth.

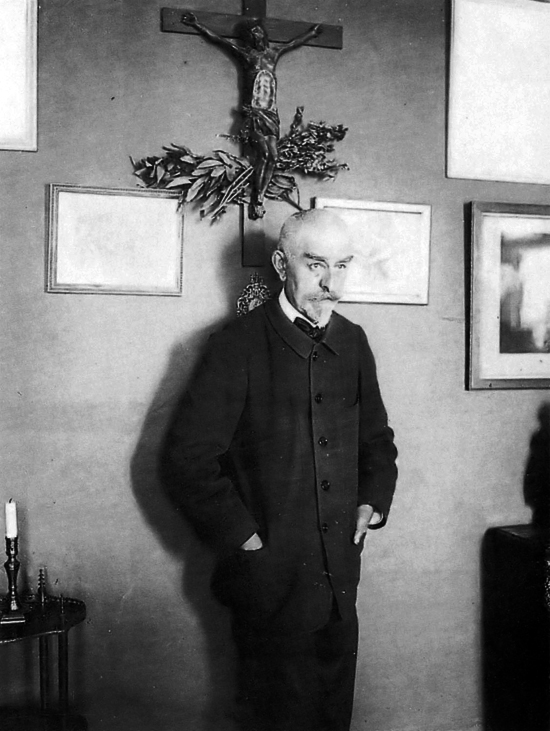

…not much longer to live. His sufferings were atrocious. ‘It was’, says Dom Dubourg, ‘with a sentiment of religious respect that, in his study on the fifth floor, so far from the earth and so near to the heavens, I discovered our dear friend in his usual surroundings, in the middle of the books he could no longer read, having before him a page of manuscript he could no longer finish. His features were emaciated, deformed by the malady from which he suffered, but illuminated from time to time by the sweet and limpid look which he directed on his crucifix. In the middle of the agonies which were tearing him to pieces… his lips never ceased to murmur their tireless fiat…

************

To the doctors who wanted to give him morphia to ease the pain, he cried: “Ah! You want to prevent me from suffering! You want to change the sufferings of the good God for the evil pleasures of earth! I will not let you.” As Lent drew to its close, he said to me: “I have had a beautiful dream: how I wished it could be realized. I was on the cross with Jesus. Ah! if my good Master would take me, as he did the Penitent Thief, on Good Friday!” His wish was not granted. He had to drink the cup of suffering to the dregs.’

************

He…suffered martyrdom for the last eighteen months; his eyes, his ears, his teeth have, in turn, tortured him. Almost all his teeth had been extracted and his throat and mouth were nothing but a purulent wound.’

When the good Father sympathised with him he said: ‘Do not pity me. I am far from being unhappy.’ ‘It was necessary for me to suffer all this in order that those who read my books should know that I was not just “making literature”.” Certainly in his last days his faith was passionately sincere.

‘The First Decadent: J.K. Huysmans’ written by James Laver

Recent Comments