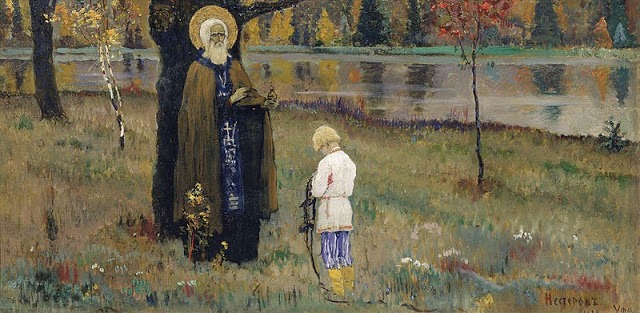

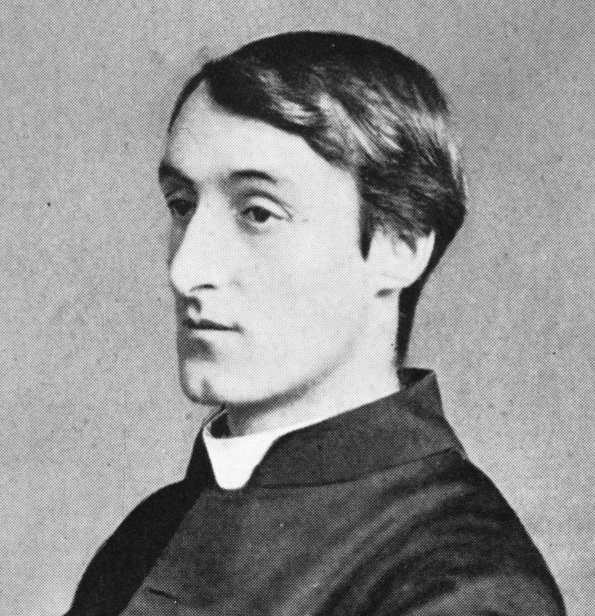

I am rereading Dostoyevsky’s brilliant novel, finding chapter 5 in Book 2 compelling, indistinctly touching upon my revulsion with the Pro-Life aspect of the Church, as well as Traditionalist. I am not clear in my ideas, highly attracted to the thought of the religious elder Father Zosima, Alyosha the youngest brother’s teacher, recognizing the fact, though determined, I have never been one of high intellect–modest in my expectations, accepting my ideas are not important. Somewhere within the barrage of ideas spewed out by various characters are thoughts of immense depth and originality–a totality coming into being. Miusov, the socialist ‘European’ intellectual, is no straw dog–a man of remarkable education and accomplishment. A man willing to commit to his ideas, raising Dimitri, one of the Brothers Karamazov, due to Fyodor being Fyodor. The discussion is opened by Ivan, the rationalist, first born son of Fyodor with his wife of elopement who left the drunken buffoon for a seminary student only to die in St Petersburg shortly afterwards. Within the imbroglio exists the reality that our best laid plans can be dissected and defeated by others. There must be something greater than being right. It is Dostoyevsky’s brilliance to illuminate truth with a vast array of deeply defined characters.

“The whole point of my article lies in the fact that during the first three centuries Christianity only existed on earth in the Church and was nothing but the Church. When the pagan Roman Empire desired to become Christian, it inevitably happened that, by becoming Christian, it included the Church but remained a pagan State in very many of its departments. In reality this was bound to happen. But Rome as a State retained too much of the pagan civilization and culture, as, for example, in the very objects and fundamental principles of the State. The Christian Church entering into the State could, of course, surrender no part of its fundamental principles—the rock on which it stands—and could pursue no other aims than those which have been ordained and revealed by God Himself, and among them that of drawing the whole world, and therefore the ancient pagan State itself, into the Church. In that way (that is, with a view to the future) it is not the Church that should seek a definite position in the State, like ‘every social organization,’ or as ‘an organization of men for religious purposes’ (as my opponent calls the Church), but, on the contrary, every earthly State should be, in the end, completely transformed into the Church and should become nothing else but a Church, rejecting every purpose incongruous with the aims of the Church. All this will not degrade it in any way or take from its honor and glory as a great State, nor from the glory of its rulers, but only turns it from a false, still pagan, and mistaken path to the true and rightful path, which alone leads to the eternal goal. This is why the author of the book On the Foundations of Church Jurisdiction would have judged correctly if, in seeking and laying down those foundations, he had looked upon them as a temporary compromise inevitable in our sinful and imperfect days. But as soon as the author ventures to declare that the foundations which he predicates now, part of which Father Iosif just enumerated, are the permanent, essential, and eternal foundations, he is going directly against the Church and its sacred and eternal vocation. That is the gist of my article.”

“That is, in brief,” Father Païssy began again, laying stress on each word, “according to certain theories only too clearly formulated in the nineteenth century, the Church ought to be transformed into the State, as though this would be an advance from a lower to a higher form, so as to disappear into it, making way for science, for the spirit of the age, and civilization. And if the Church resists and is unwilling, some corner will be set apart for her in the State, and even that under control—and this will be so everywhere in all modern European countries. But Russian hopes and conceptions demand not that the Church should pass as from a lower into a higher type into the State, but, on the contrary, that the State should end by being worthy to become only the Church and nothing else. So be it! So be it!”

“Well, I confess you’ve reassured me somewhat,” Miüsov said smiling, again crossing his legs. “So far as I understand, then, the realization of such an ideal is infinitely remote, at the second coming of Christ. That’s as you please. It’s a beautiful Utopian dream of the abolition of war, diplomacy, banks, and so on—something after the fashion of socialism, indeed. But I imagined that it was all meant seriously, and that the Church might be now going to try criminals, and sentence them to beating, prison, and even death.”

“But if there were none but the ecclesiastical court, the Church would not even now sentence a criminal to prison or to death. Crime and the way of regarding it would inevitably change, not all at once of course, but fairly soon,” Ivan replied calmly, without flinching.

“Are you serious?” Miüsov glanced keenly at him.

“If everything became the Church, the Church would exclude all the criminal and disobedient, and would not cut off their heads,” Ivan went on. “I ask you, what would become of the excluded? He would be cut off then not only from men, as now, but from Christ. By his crime he would have transgressed not only against men but against the Church of Christ. This is so even now, of course, strictly speaking, but it is not clearly enunciated, and very, very often the criminal of to‐day compromises with his conscience: ‘I steal,’ he says, ‘but I don’t go against the Church. I’m not an enemy of Christ.’ That’s what the criminal of to‐day is continually saying to himself, but when the Church takes the place of the State it will be difficult for him, in opposition to the Church all over the world, to say: ‘All men are mistaken, all in error, all mankind are the false Church. I, a thief and murderer, am the only true Christian Church.’ It will be very difficult to say this to himself; it requires a rare combination of unusual circumstances. Now, on the other side, take the Church’s own view of crime: is it not bound to renounce the present almost pagan attitude, and to change from a mechanical cutting off of its tainted member for the preservation of society, as at present, into completely and honestly adopting the idea of the regeneration of the man, of his reformation and salvation?”

“What do you mean? I fail to understand again,” Miüsov interrupted. “Some sort of dream again. Something shapeless and even incomprehensible. What is excommunication? What sort of exclusion? I suspect you are simply amusing yourself, Ivan Fyodorovitch.”

“Yes, but you know, in reality it is so now,” said the elder suddenly, and all turned to him at once. “If it were not for the Church of Christ there would be nothing to restrain the criminal from evil‐doing, no real chastisement for it afterwards; none, that is, but the mechanical punishment spoken of just now, which in the majority of cases only embitters the heart; and not the real punishment, the only effectual one, the only deterrent and softening one, which lies in the recognition of sin by conscience.”

“How is that, may one inquire?” asked Miüsov, with lively curiosity.

“Why,” began the elder, “all these sentences to exile with hard labor, and formerly with flogging also, reform no one, and what’s more, deter hardly a single criminal, and the number of crimes does not diminish but is continually on the increase. You must admit that. Consequently the security of society is not preserved, for, although the obnoxious member is mechanically cut off and sent far away out of sight, another criminal always comes to take his place at once, and often two of them. If anything does preserve society, even in our time, and does regenerate and transform the criminal, it is only the law of Christ speaking in his conscience. It is only by recognizing his wrong‐doing as a son of a Christian society—that is, of the Church—that he recognizes his sin against society—that is, against the Church. So that it is only against the Church, and not against the State, that the criminal of to‐day can recognize that he has sinned. If society, as a Church, had jurisdiction, then it would know when to bring back from exclusion and to reunite to itself. Now the Church having no real jurisdiction, but only the power of moral condemnation, withdraws of her own accord from punishing the criminal actively. She does not excommunicate him but simply persists in motherly exhortation of him. What is more, the Church even tries to preserve all Christian communion with the criminal. She admits him to church services, to the holy sacrament, gives him alms, and treats him more as a captive than as a convict. And what would become of the criminal, O Lord, if even the Christian society—that is, the Church—were to reject him even as the civil law rejects him and cuts him off? What would become of him if the Church punished him with her excommunication as the direct consequence of the secular law? There could be no more terrible despair, at least for a Russian criminal, for Russian criminals still have faith. Though, who knows, perhaps then a fearful thing would happen, perhaps the despairing heart of the criminal would lose its faith and then what would become of him? But the Church, like a tender, loving mother, holds aloof from active punishment herself, as the sinner is too severely punished already by the civil law, and there must be at least some one to have pity on him. The Church holds aloof, above all, because its judgment is the only one that contains the truth, and therefore cannot practically and morally be united to any other judgment even as a temporary compromise. She can enter into no compact about that. The foreign criminal, they say, rarely repents, for the very doctrines of to‐day confirm him in the idea that his crime is not a crime, but only a reaction against an unjustly oppressive force. Society cuts him off completely by a force that triumphs over him mechanically and (so at least they say of themselves in Europe) accompanies this exclusion with hatred, forgetfulness, and the most profound indifference as to the ultimate fate of the erring brother. In this way, it all takes place without the compassionate intervention of the Church, for in many cases there are no churches there at all, for though ecclesiastics and splendid church buildings remain, the churches themselves have long ago striven to pass from Church into State and to disappear in it completely. So it seems at least in Lutheran countries. As for Rome, it was proclaimed a State instead of a Church a thousand years ago. And so the criminal is no longer conscious of being a member of the Church and sinks into despair. If he returns to society, often it is with such hatred that society itself instinctively cuts him off. You can judge for yourself how it must end. In many cases it would seem to be the same with us, but the difference is that besides the established law courts we have the Church too, which always keeps up relations with the criminal as a dear and still precious son. And besides that, there is still preserved, though only in thought, the judgment of the Church, which though no longer existing in practice is still living as a dream for the future, and is, no doubt, instinctively recognized by the criminal in his soul. What was said here just now is true too, that is, that if the jurisdiction of the Church were introduced in practice in its full force, that is, if the whole of the society were changed into the Church, not only the judgment of the Church would have influence on the reformation of the criminal such as it never has now, but possibly also the crimes themselves would be incredibly diminished. And there can be no doubt that the Church would look upon the criminal and the crime of the future in many cases quite differently and would succeed in restoring the excluded, in restraining those who plan evil, and in regenerating the fallen. It is true,” said Father Zossima, with a smile, “the Christian society now is not ready and is only resting on some seven righteous men, but as they are never lacking, it will continue still unshaken in expectation of its complete transformation from a society almost heathen in character into a single universal and all‐powerful Church. So be it, so be it! Even though at the end of the ages, for it is ordained to come to pass! And there is no need to be troubled about times and seasons, for the secret of the times and seasons is in the wisdom of God, in His foresight, and His love. And what in human reckoning seems still afar off, may by the Divine ordinance be close at hand, on the eve of its appearance. And so be it, so be it!”

“So be it, so be it!” Father Païssy repeated austerely and reverently.

“Strange, extremely strange!” Miüsov pronounced, not so much with heat as with latent indignation.

“What strikes you as so strange?” Father Iosif inquired cautiously.

“Why, it’s beyond anything!” cried Miüsov, suddenly breaking out; “the State is eliminated and the Church is raised to the position of the State. It’s not simply Ultramontanism, it’s arch‐Ultramontanism! It’s beyond the dreams of Pope Gregory the Seventh!”

“You are completely misunderstanding it,” said Father Païssy sternly. “Understand, the Church is not to be transformed into the State. That is Rome and its dream. That is the third temptation of the devil. On the contrary, the State is transformed into the Church, will ascend and become a Church over the whole world—which is the complete opposite of Ultramontanism and Rome, and your interpretation, and is only the glorious destiny ordained for the Orthodox Church. This star will arise in the east!”

Miüsov was significantly silent. His whole figure expressed extraordinary personal dignity. A supercilious and condescending smile played on his lips. Alyosha watched it all with a throbbing heart. The whole conversation stirred him profoundly. He glanced casually at Rakitin, who was standing immovable in his place by the door listening and watching intently though with downcast eyes. But from the color in his cheeks Alyosha guessed that Rakitin was probably no less excited, and he knew what caused his excitement.

“Allow me to tell you one little anecdote, gentlemen,” Miüsov said impressively, with a peculiarly majestic air. “Some years ago, soon after the coup d’état of December, I happened to be calling in Paris on an extremely influential personage in the Government, and I met a very interesting man in his house. This individual was not precisely a detective but was a sort of superintendent of a whole regiment of political detectives—a rather powerful position in its own way. I was prompted by curiosity to seize the opportunity of conversation with him. And as he had not come as a visitor but as a subordinate official bringing a special report, and as he saw the reception given me by his chief, he deigned to speak with some openness, to a certain extent only, of course. He was rather courteous than open, as Frenchmen know how to be courteous, especially to a foreigner. But I thoroughly understood him. The subject was the socialist revolutionaries who were at that time persecuted. I will quote only one most curious remark dropped by this person. ‘We are not particularly afraid,’ said he, ‘of all these socialists, anarchists, infidels, and revolutionists; we keep watch on them and know all their goings on. But there are a few peculiar men among them who believe in God and are Christians, but at the same time are socialists. These are the people we are most afraid of. They are dreadful people! The socialist who is a Christian is more to be dreaded than a socialist who is an atheist.’ The words struck me at the time, and now they have suddenly come back to me here, gentlemen.”

“You apply them to us, and look upon us as socialists?” Father Païssy asked directly, without beating about the bush.

But before Pyotr Alexandrovitch could think what to answer, the door opened, and the guest so long expected, Dmitri Fyodorovitch, came in. They had, in fact, given up expecting him, and his sudden appearance caused some surprise for a moment.

Recent Comments