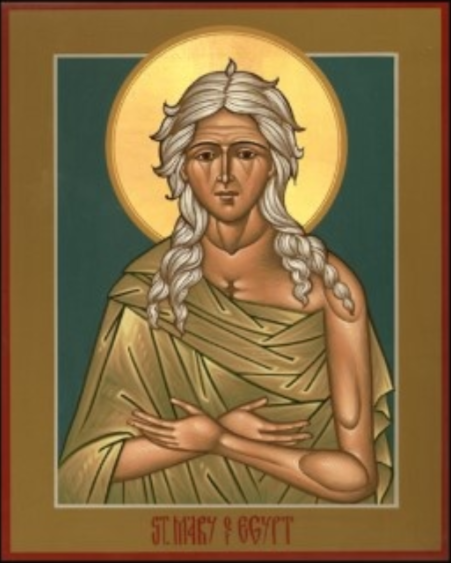

“O Lady, Mother of God, who gave birth in the flesh to God the Word, I know, O how well I know, that it is no honour or praise to thee when one so impure and depraved as I look up to thy icon, O ever-virgin, who didst keep thy body and soul in purity. Rightly do I inspire hatred and disgust before thy virginal purity. But I have heard that God Who was born of thee became man on purpose to call sinners to repentance. Then help me, for I have no other help. Order the entrance of the church to be opened to me. Allow me to see the venerable Tree on which He Who was born of thee suffered in the flesh and on which He shed His holy Blood for the redemption of sinners and for me, unworthy as I am. Be my faithful witness before thy son that I will never again defile my body by the impurity of fornication, but as soon as I have seen the Tree of the Cross I will renounce the world and its temptations and will go wherever thou wilt lead me.”

The perfect joy of St Francis always appealed to me, yet a recent reading and reflection advanced the charming story to an understanding of living within honesty, forsaking dreams and delusion. Dreams and delusion too often steer the mind toward glorification of one’s self, a doing of great things, a usurping of the will of God, the advancement of individuality preventing one from living within the moment, reality rejected for the sake of possibilities, uncompliant with one’s current standing. There are enough people doing great things. The story is a bit dramatic, cunning with insight. The grandeur of accepting the sufferings of daily life ultimately providing the greatest of joys, the development of discipline leading to a concentration upon Christ within the individuality of our lives, is playfully exercised.

How Saint Francis, walking one day with brother Leo, explained to him what things are perfect joy.

One day in winter, as Saint Francis was going with Brother Leo from Perugia to Saint Mary of the Angels, and was suffering greatly from the cold, he called to Brother Leo, who was walking on before him, and said to him: “Brother Leo, if it were to please God that the Friars Minor should give, in all lands, a great example of holiness and edification, write down, and note carefully, that this would not be perfect joy.”

A little further on, Saint Francis called to him a second time: “O Brother Leo, if the Friars Minor were to make the lame to walk, if they should make straight the crooked, chase away demons, give sight to the blind, hearing to the deaf, speech to the dumb, and, what is even a far greater work, if they should raise the dead after four days, write that this would not be perfect joy.”

Shortly after, he cried out again: “O Brother Leo, if the Friars Minor knew all languages; if they were versed in all science; if they could explain all Scripture; if they had the gift of prophecy, and could reveal, not only all future things, but likewise the secrets of all consciences and all souls, write that this would not be perfect joy.”

After proceeding a few steps farther, he cried out again with a loud voice: “O Brother Leo, thou little lamb of God! if the Friars Minor could speak with the tongues of angels; if they could explain the course of the stars; if they knew the virtues of all plants; if all the treasures of the earth were revealed to them; if they were acquainted with the various qualities of all birds, of all fish, of all animals, of men, of trees, of stones, of roots, and of waters – write that this would not be perfect joy.”

Shortly after, he cried out again: “O Brother Leo, if the Friars Minor had the gift of preaching so as to convert all infidels to the faith of Christ, write that this would not be perfect joy.”

Now when this manner of discourse had lasted for the space of two miles, Brother Leo wondered much within himself; and, questioning the saint, he said: “Father, I pray thee teach me wherein is perfect joy.”

Saint Francis answered: “If, when we shall arrive at Saint Mary of the Angels, all drenched with rain and trembling with cold, all covered with mud and exhausted from hunger; if, when we knock at the convent-gate, the porter should come angrily and ask us who we are; if, after we have told him, “We are two of the brethren”, he should answer angrily, “What ye say is not the truth; ye are but two impostors going about to deceive the world, and take away the alms of the poor; begone I say”; if then he refuse to open to us, and leave us outside, exposed to the snow and rain, suffering from cold and hunger till nightfall – then, if we accept such injustice, such cruelty and such contempt with patience, without being ruffled and without murmuring, believing with humility and charity that the porter really knows us, and that it is God who makes him speak against us, write down, O Brother Leo, that this is perfect joy.

And if we knock again, and the porter comes out in anger to drive us away with oaths and blows, as if we were vile impostors, saying, “Begone, miserable robbers! You shall neither eat nor sleep!” – and if we accept all this with patience, with joy, and with charity, O Brother Leo, write that this indeed is perfect joy.

And if, urged by cold and hunger, we knock again, calling to the porter and entreating him with many tears to open to us and give us shelter, for the love of God, and if he come out more angry than before, exclaiming, “These are but importunate rascals, I will deal with them as they deserve”; and taking a knotted stick, he seize us by the hood, throwing us on the ground, rolling us in the snow, and shall beat and wound us with the knots in the stick – if we bear all these injuries with patience and joy, thinking of the sufferings of our Blessed Lord, which we would share out of love for him, write, O Brother Leo, that here, finally, is perfect joy.

And now, brother, listen to the conclusion. Above all the graces and all the gifts of the Holy Spirit which Christ grants to his friends, is the grace of overcoming oneself, and accepting willingly, out of love for Christ, all suffering, injury, discomfort and contempt; for in all other gifts of God we cannot glory, seeing they proceed not from ourselves but from God, according to the words of the Apostle, “What hast thou that thou hast not received from God? and if thou hast received it, why dost thou glory as if thou had not received it?” But in the cross of tribulation and affliction we may glory, because, as the Apostle says again, “I will not glory save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Amen.”

To the praise and glory of Jesus Christ and his poor servant Francis. Amen.

O Savior, rend the heavens wide;

Come down, come down with mighty stride;

Unlock the gates, the doors break down;

Unbar the way to heaven’s crown.

O Morning Star, O radiant Dawn,

When will we sing your morning song?

Come, Son of God! Without your light

We grope in dread and gloom of night.

Sin’s dreadful doom upon us lies;

Grim death looms fierce before our eyes.

Oh, come, lead us with mighty hand

From exile to our promised land.

There shall we all our praises bring

And sing to you, our Savior King;

There shall we laud you and adore

Forever and forevermore.

An Advent Wreath I put together. The candles were purchased from Root Candle outlet store in Medina, Ohio. The wreath and candle holders were bought at Seconds City, a consignment store in Middleburg Heights. Everything cost under $20.

No early Saturday Mass and Holy Hour at St Dominic this morning. I learned the fact after arriving. It sent me to Sacred Heart, and thus the discovery the men’s group I use to be involved with was conducting a session after Mass. The men meet monthly on the second and fourth Saturdays. I proved to be a meaningful experience. Starting the session with bagels, orange juice, and familiarizing fellowship, I realized how much I enjoyed the men, individuals emerging distinct. Initial and final discussion, centered upon Roger Freedman, an electrician I knew from St Paul Shrine who passed away two years ago during the Advent season. Roger was a regular member of the group, rarely missing a meeting. His wife is still active at St Paul Shrine and all the men relished in reminiscing about Roger. I commented on a comment about Roger during his funeral Mass, as a deacon made a powerful statement perfectly describing his personality. The deacon said, ‘Roger was always happy to see you, even when he was not’. A whimsical way of defining Roger’s amiable and outgoing nature that never expressed negativity, nor confrontation toward others. He was truly a kind and considerate man. The Sacred Heart men’s group starts their sessions singing three hymns, allowing a harmonizing and unifying of voices to tenderize personalities. They advance to a communal psalm prayer, similar to a religious community exercising the Liturgy of the Hours, followed by the sabbath scriptural reading for the coming Sunday. Today’s reading covered the final week of the liturgical year, the celebration of the Kingship of Jesus Christ. After the reading of lectionary scripture, we will listen to a commentary on the readings by Bishop Robert Barron. Today, Bishop Barron moved me with the creation of an image of Jesus warring during His Passion and Crucifixion. Jesus was not a passive victim being executed. He was a King battling through the conquering of the world and death. Once the Bishop has spoken, the meeting is opened to comments from the attending men. I am always impressed by the maturity, humility, and seriousness of the group. There are differences, yet everyone is listened to, and the prayerful nature of the beginning carries over into personal thoughts and opinions. We end with a final hymn, everyone singing together. It was a wonderful time of manly fellowship. One man in particular draws my attention. He is a writer, a bit of an agitator—poking at conservative Catholics and those who tend to point a finger of blame at others. He is actively involved in prison ministry. Prosperous, respected for his gardening skills, and advancing into his elderly years, the articulate and intelligent man served a prison sentence himself when younger. I believe he was imprisoned for just over five years. I may visit with him at his home this coming week. God is good and all giving.

Arch-Bishop Charles J. Chaput from ‘Strangers in a Strange Land’

Over the course of decades, Peck (psychiatrist/author of ‘People of the Lie’) met patients who didn’t fit a standard diagnosis but had certain recurring traits. These persons showed chronic disregard for the good of others to the point of causing grave psychological harm. They were subtly but pervasively self-centered. Their symptoms were broader than narcissistic personality disorder, but they weren’t sociopaths. They knew right from wrong.

…their main shared trait was the habit of lying. They all lied constantly and effortlessly about everything—especially about themselves, to themselves. As such, they were opaque even to highly trained therapists. More important, they were opaque to themselves. For Peck, the “layer upon layer of self- deception” that “people of the lie” build up insulates them so thoroughly from truth that they no longer recognize it. Their own irreproachability is their only truth.

Peck didn’t mince words. He calls such persons evil.,,,”evil” people erect so many defenses against self-examination and repentance that these become almost impossible without a miracle of grace.

“People of the lie” embody Aristotle’s teachings on the formation of character. They don’t wake up one morning and decide to be cruel. Rather, they accumulate years of decisions to ignore the true good in favor of their own apparent good, until they fully identify their own will with what’s genuinely good.

As Peck notes, this reveals itself as a preoccupation with appearances: “While they seem to lack any motivation to be good, they intensely desire to appear good. Their ‘goodness’ is all on a level of pretense. It is, in effect, a lie”. The evasion of truth soon makes their entire lives little more than an intricate ruse.

For these morally crippled creatures, the pretense of goodness salves the scars of conscience that do exist, but that have been routinely ignored and abused. “The central defect of the evil [person] is not the sin but the refusal to acknowledge it.” We all sin, of course, but the unwillingness to take any responsibility for our sins implies a more deeply damaged spirit. And so the evil person doubles down on his or her lies by cultivating false appearances and scapegoating the innocent.

As Peck puts it, “We become evil by attempting to hide from ourselves. The wickedness of the evil is not committed directly, but indirectly as part of [the] cover-up process. Evil originates not in the absence of guilt but in the effort to escape it.

One of the most striking case studies in People of the Lie is that of a wealthy couple whose teenage son suffers from depression. As Peck probed the cause of the son’s depression with the boy and his parents, the adults avoided even a hint of responsibility for his mental state. They ignored both their son’s needs and Peck’s advice, and then shifted the burden for their own self-serving decisions back onto the boy and his doctor. After the son acted out by taking part in a petty theft at school, his parents pressed to have him diagnosed as a genetically predisposed and thus incurable criminal.

The story ends with a letter from the boy’s mother informing Peck that they had followed his kind advice and sent their son to a military boarding school. The punchline: This was exactly the opposite of Peck’s counsel. The parents had washed their hands of responsibility for their own son. Any problems would henceforward be the fault of the school or the doctor, but never them. Rather than face their self-deception and damage the illusion of their own goodness, they lied to Peck and further harmed their son.

“People of the lie” don’t reject the idea of all sin—only their own. They’re quite willing to condemn others. In fact, as Peck points out, scapegoating is one of the universal traits of “people of the lie.” They project their own guilt, which they feel but won’t accept, onto others. “Rather than blissfully lacking a sense of morality like the psychopath, they are continually engaged in sweeping the evidence of their evil under the rug of their own consciousness.

A person wrapped in deception does not blind himself to sin. He blinds himself to the possibility of forgiveness. In refusing any obligations to truth outside of himself, he closes himself off to the mercy of God. Dr. Peck puts in psychological terms what believers know by faith: “Mental health requires that the human will submit itself to something higher than itself. To function decently in the world, we must submit ourselves to some principle that takes precedence over what we might want at any given moment. For [religious persons] this principle is God, and so they will say, ‘Thy will, not mine, be done.

We typically think of this submission as an act of obedience to God’s will, as Peck mentions. But it’s actually a submission to God’s love and mercy. This requires, of course, admitting our own sinfulness. The spurning of forgiveness is the most self-poisoning symptom of the “people of the lie,” and the source of their despair.

In discussing ‘People of the Lie’, it’s easy to use the words “they” and “them.” But what’s bracing about Scott Peck’s work is that it implicates all of us and our wider culture. The pretense of goodness, the perversely moralistic scapegoating, the self-deception—these aren’t just the sins of “evil” people. They’re qualities rooted in our fallen nature and pandemic in a society based on license. We’re all, to some degree, “people of the lie.”

Dr. Peck wrote about extreme cases, but we should see them as warnings to heed, not specimens to gawk at. The feckless parents discussed above weren’t born with a resentment of the truth. Rather, they nourished it with thousands of little untruths. They developed alibis and habits of deception, especially self-deception, that over many years formed their character. Every one of us is prone to the same process. It’s up to us to see and arrest it before it begins.

That’s not so simple. We live in a culture eager to make truth a boutique experience as malleable as our personal tastes require. As the moral philosopher Harry Frankfurt writes, a vast and congenial river of baloney, humbug, and mumbo-jumbo flows through American culture that has its source in “various forms of skepticism which deny that we can have any reliable access to an objective reality, and which therefore reject the possibility of knowing how things truly are.” But we need to remember what—or rather who—comprises the culture. Things we can’t control do often impact our personal decisions. But the fact remains that “the culture” is little more than the sum of the choices, habits, and dispositions of the people who live in a particular place at a particular time. We can’t simply blame “the culture.” We are the culture.

Failing to cultivate a taste for truth, then, is an abdication of our duties not just to God, but also to one another. By contributing to a culture that seeks to invent its own truth, we make it harder for others to find the real thing. The results are deeply damaging. Subcultures of deceit emerge in places within our society where honesty is most important.

Recent Comments