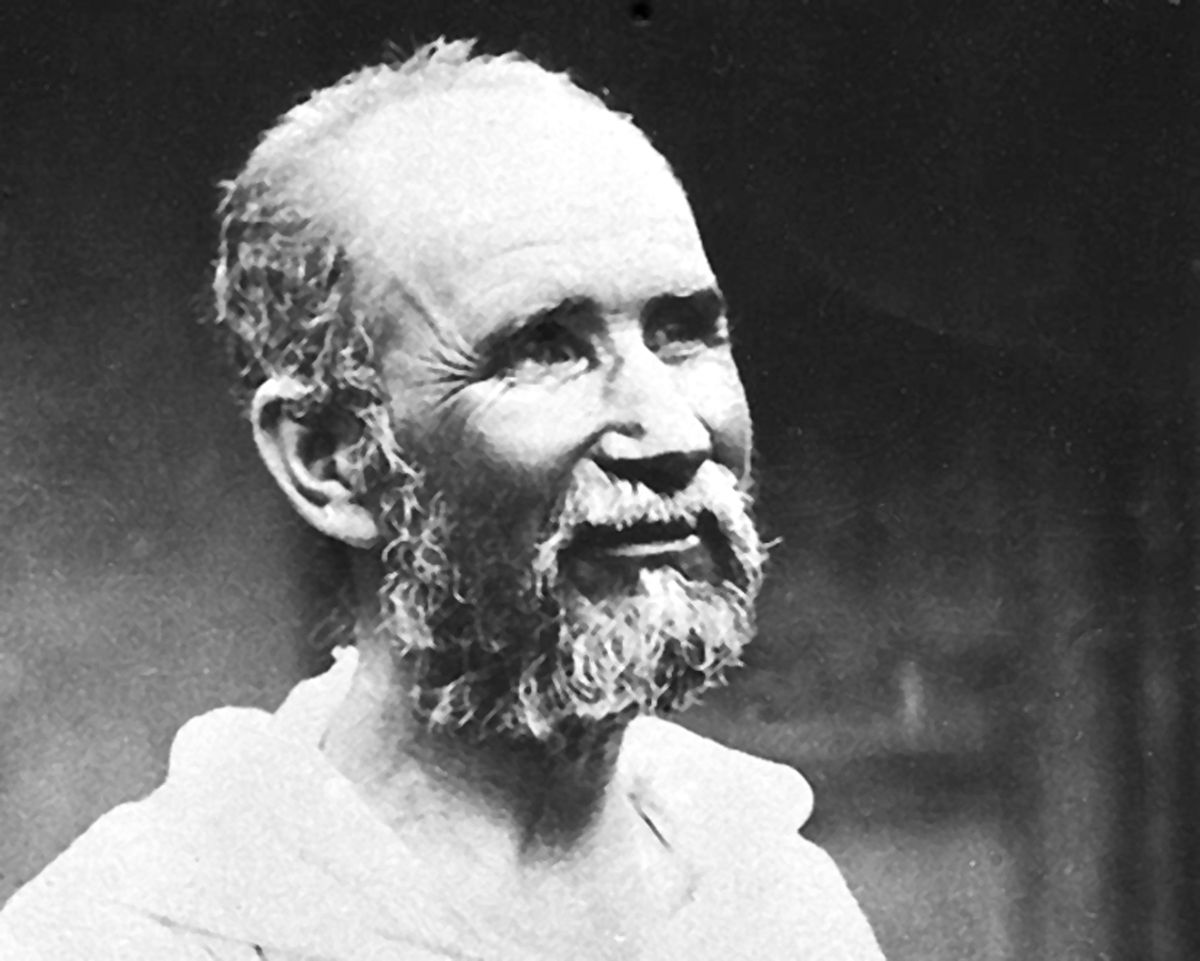

Once again the delightfully charming antics and events in the life of Charles de Foucauld brought a spiritual smile to my heart. This French man could definitely be the hilarious younger brother of the Blessed Henry Suso. I cannot say how much he reminds me of a quirky wonderful holy Catholic Lebanese man from Toledo, Jim Saad. I roared with laughter when reading the following:

Foucauld’s idea had been that he would ‘live there (Poor Clare community in Nazareth) without anyone knowing who I was, as the workman living by his daily labours’. Unfortunately, this was not how things turned out. His labours’ costume, which consisted of turban sandals and blue cotton pajamas wrapped around with a wide leather belt from which hung an outsize rosary, made him an object of instant curiosity. Gratifyingly, he was able to horrify a young European woman: ‘I am so scared of vermin’, she said to her husband as Foucauld drew near. The Poor Clares soon discovered who this curiously dressed man really was. And it became rapidly apparent that his laboring skills were minimal: having witnessed his attempts at wall-building, carpentry, and gardening, the Poor Clares assigned him to sweeping and fetching the mail. His own description of life in Nazareth hardly conformed to any recognizable image of labor: ‘very often I draw little pictures for the sisters. If there are any small jobs I do them, but this is rare; generally I spend the whole day doing little things in my room.’ Nevertheless, he believed he had broken successfully into a working man’s existence. He wrote triumphantly of how he had arrived ‘without any papers but my passport, and on the sixth day I found that only a means of earning my living but also earning it under just the conditions I had been dreaming of for so many years; it seemed as though this place was waiting for me, and indeed it was waiting for me, for nothing happens by chance, and everything that happens has been prepared by God; I am a servant, the domestic, the valet, of a poor religious community.’

The Poor Clares treated him with a benevolent respect. They did not demur when he turned down their offer of accommodations, opting instead to sleep in a small tool shed overlooking a paddock. Nor did they insist, beyond a delicate suggestion that a bowl of soup might be fortifying, that he except any more than the dried bread, twice a day, which he asked as his wage. They maintained his own pretense that he was a simple nobody and did not mind when he seemed unable to do anything beyond the most trivial chores. There were occasions, however, when outsiders were surprised by Foucauld’s behavior. A visiting bishop became intolerant at his continual fawning and demanded he be sent back to work; another was amazed at his attempts to cut his own hair and assumed he had ringworm; a third was bewildered when, on asking why he looked so happy, he received the answer that children had thrown stones at him in the street. His confessor, the only person who saw him on a regular basis other than the Poor Clares, remarked that ‘He is a very good boy, but not one of the most intelligent.’

If Foucauld seemed unintelligent it was probably because his confessor judged him by conventional standards. Foucauld was perfectly rational, he could make incisive political comments when he felt like it, and he retained enough military expertise for the Poor Clares to give him a shot gun to defend their hen-run. But he was not interested in rationality, politics or guns. His self-declared aim was ‘a deeper dispossession and a greater lowliness so that I might be still more like Jesus.’ –Fergus Fleming ‘The Sword and the Cross: Two Men and an Empire of Sand’