Last Illness and Death

John of the Cross had been deprived of all power and office. His cell was bare, and no entertainment, comfort, or consolation was at hand. He was again a humble friar–as humble and as poor as when he had started on the road to perfection in the hut at Duruelo. The only difference now was that he knew he did not have much time left. Although he had written from La Penuela that his sickness was trivial and that he would recover in a short time, he must have known that his strength had been sapped. Even the unfriendly Prior noticed that something was seriously wrong and had a doctor called.

When Antonio de Villarreal, a physician in town, arrived the next morning, the five sores in John’s foot had burst. Pus and blood were oozing. The doctor saw the need to open the ulcers and drain them. Without anesthetic, he proceeded to cut a deep incision, reaching the bone. The operation gave some relief but John of the Cross had to lie in bed. In the following days, he lay alone. The Prior visited him only to upbraid him and accuse him of a hundred imaginary crimes and imperfections. He ordered the brothers not to go near him. When charitable ladies in town offered their services to wash the sick man’s linen and change the dressing of his wounds, the Prior refused his permission. He did not allow the townspeople to provide food for Saint John’s sustenance.

The Prior of La Penuela and many of the friars were grieved when they learned of the cruel treatment John was subjected to. They found ways to inform the Provincial, who was the very old and venerable Friar Antonio de Jesus, John’s former prior in Duruelo. Antonio hastened to visit his old friend. When he saw the truth of the report, he censured the Prior of Ubeda and ordered some comfort of music and nourishment for John of the Cross. During the few days of his stay at Ubeda, Friar Antonio tried to cheer John, whom he visited often. After he left, since his example and his admonitions had succeeded in convincing the community that John deserved sympathy and love, the friars tried to console and help him, and even the Prior relented in his treatment of the dying friar.

It was, alas, too late. John himself begged that no music be played: he did not want to be distracted from the pain he thought was given to him for purification. As he lay in bed, his body began to be covered with sores. First, two large ulcers were found on his back and were opened. Then a large sore developed between his shoulder blades. More sores covered his body, and the inflammation in his leg grew worse in spite of surgery.

In the first days of December, the physician made it clear to John that he could not hope to recover. He had only days to live. The last test was at hand. The remaining days he spent reading or listening to passages of religious books read to him. Occasionally, he would listen to music or to the recitation of his own verses that promised the return of rapture he had known in moments off meditation and fervor. He continued to reflect on the futility of all things human and to long for the bliss he had named in enigmatic words during the suffering in his cell.

He knew now he would soon be delivered from the last imprisonment. On the night of the 14th of December of 1591, after having prepared his soul through confession and communion, consoled with sweet conversation from the young priests who had come to his side, his time in the world was completed. Everybody was shaken, while John of the Cross was serene and happy. The distant murmur of matins could be heard when John ceased his exhortations for the last time. Those who had heard him knew he had just paused in his work. The words he had repeated so often were now to be repeated without the changes of his inflexion and reworking; they belonged to the world now. The thoughts and the rhythms he had left in manuscripts were copied by disciples who remembered him in the convents at Beas or Granada. His example lived on in the memory of those who had loved him. Many years later their manuscripts were to be printed, and the words he had uttered were to become all that was left of him.

John of the Cross had lived less than fifty years. Of the external experiences of success and power he had known little or nothing. Of poverty and suffering he had known as much as man can know. From childhood to adolescence, from youth to manhood and maturity, he had been schooled in pain and renunciation. He had had as many opportunities as any man in his time and place to grab security or worldly gain, but had spurned every chance. He had instead been steadfast and loyal to his one ambition: to learn and to understand. He had been ill since adolescence and had suffered from unexplained fevers and excruciating pains. But his will had conquered pain and disease, poverty and calumny, temptation and power. What was left of him was only the light of a thought so clear that generation after generation would return to it again and again.

San Juan De La Cruz biography and commentary by Bernard Gicovate

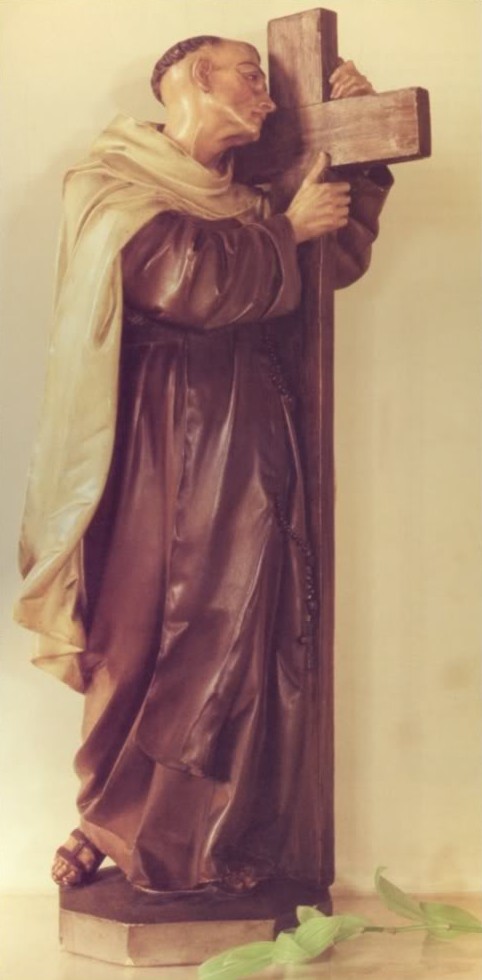

St John of the Cross Adoring