He raised his head, thought a minute, and began with enthusiasm:

“Wild and fearful in his cavern

Hid the naked troglodyte,

And the homeless nomad wandered

Laying waste the fertile plain.

Menacing with spear and arrow

In the woods the hunter strayed….

Woe to all poor wretches stranded

On those cruel and hostile shores!

“From the peak of high Olympus

Came the mother Ceres down,

Seeking in those savage regions

Her lost daughter Proserpine.

But the Goddess found no refuge,

Found no kindly welcome there,

And no temple bearing witness

To the worship of the gods.

“From the fields and from the vineyards

Came no fruits to deck the feasts,

Only flesh of bloodstained victims

Smoldered on the altar‐fires,

And where’er the grieving goddess

Turns her melancholy gaze,

Sunk in vilest degradation

Man his loathsomeness displays.”

Mitya broke into sobs and seized Alyosha’s hand.

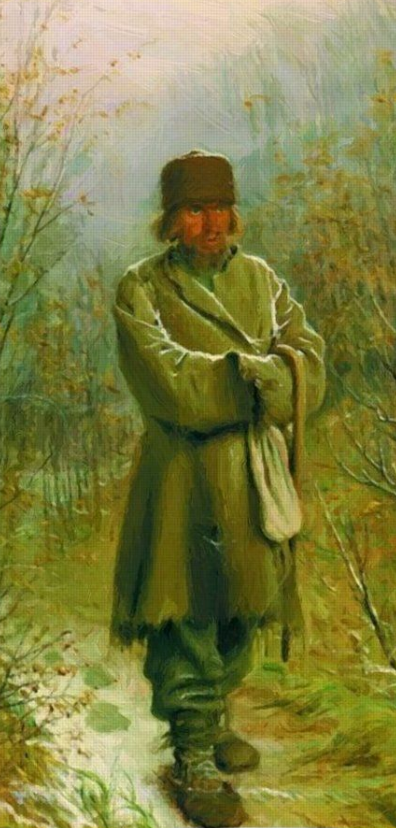

“My dear, my dear, in degradation, in degradation now, too. There’s a terrible amount of suffering for man on earth, a terrible lot of trouble. Don’t think I’m only a brute in an officer’s uniform, wallowing in dirt and drink. I hardly think of anything but of that degraded man—if only I’m not lying. I pray God I’m not lying and showing off. I think about that man because I am that man myself.

Would he purge his soul from vileness

And attain to light and worth,

He must turn and cling for ever

To his ancient Mother Earth.

But the difficulty is how am I to cling for ever to Mother Earth. I don’t kiss her. I don’t cleave to her bosom. Am I to become a peasant or a shepherd? I go on and I don’t know whether I’m going to shame or to light and joy. That’s the trouble, for everything in the world is a riddle! And whenever I’ve happened to sink into the vilest degradation (and it’s always been happening) I always read that poem about Ceres and man. Has it reformed me? Never! For I’m a Karamazov. For when I do leap into the pit, I go headlong with my heels up, and am pleased to be falling in that degrading attitude, and pride myself upon it. And in the very depths of that degradation I begin a hymn of praise. Let me be accursed. Let me be vile and base, only let me kiss the hem of the veil in which my God is shrouded. Though I may be following the devil, I am Thy son, O Lord, and I love Thee, and I feel the joy without which the world cannot stand.

Joy everlasting fostereth

The soul of all creation,

It is her secret ferment fires

The cup of life with flame.

’Tis at her beck the grass hath turned

Each blade towards the light

And solar systems have evolved

From chaos and dark night,

Filling the realms of boundless space

Beyond the sage’s sight.

At bounteous Nature’s kindly breast,

All things that breathe drink Joy,

And birds and beasts and creeping things

All follow where She leads.

Her gifts to man are friends in need,

The wreath, the foaming must,

To angels—vision of God’s throne,

To insects—sensual lust.

But enough poetry! I am in tears; let me cry……

The Brothers Karamazov. Dimitri, the eldest son, a sensualist like his father, speaking with his younger brother Alyosha, a pure religious aspirant–sons to the drunken buffoon Fyodor. Written by Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

The heart produces tears that are better connected to God as the individual becomes better connected to the love of the divine and the love of others:

And so the eye, that wishes to satisfy the heart, weeps into my love and that of its neighbor, with love of the heart, pained only for the offense done to me and the injury done to the neighbor, not for its own pain or individual injury. (Dialogo)

The love of the heart (amore cordiale) does not look within for injury, but rather looks to others. The phrase “geme nella mia carità” [weeps into my love] is notable for the suggestion that one may weep into God’s love and into the love of others. The connectedness of these tears is emphasized in the very language. It is important to note the emphasis on neighbors and on community. Compassion has been transferred from the self to the neighbor. Love is focused on a community in God, rather than on the individual.

By means of this path, the individual finds sustenance. As the intellect begins to see, understand, and know the truth that is God:

The intellect pulls the affections with it, the affections that taste my eternal divinity and in this know and see the divine nature united with humanity. And so the affections rest in me, the peaceful sea. The heart is united by the affection of love to me… in the sentiment of me, eternal God, the eye begins to pour tears of sweetness, that are a milk that directly nourishes the soul of true patience. These tears are a scented unguent that gives off a smell of great sweetness. (Dialogo)

These tears are likened to milk, to nourishment, to a divine food. The 14th-century physician, Mondino de’ Liuzzi (c. 1270-1326), explains that milk is made in the breasts from well-heated and refined blood, and it is for this reason that the breasts are located near the heart, he says, so that they may profit from the heat of this area. Here it is the eyes themselves that pour out a kind of milk, nourishing the soul. When the heart is connected to God, tears of milk emerge from it to nourish the soul that inhabits that same heart. This kind of circulation that turns back to nourish the self is justified through the heart’s unity with God. When God is present within the heart, tears do not belong to the individual alone but are rather a product of the love between that individual and God. Just as breast milk can only be produced by a female body that has been inhabited by another being, so these tears of milk can only emerge from a heart that rests within the sea that is God and is filled with the presence of the divine: and

Oh, my most adored daughter, how glorious is that soul that has managed to truly pass from the tempestuous sea to me, the peaceful sea, has filled the vessel of the heart in the sea that I am, highest and eternal God. Thus the eye, that is like a conduit that comes from the heart, seeks to satisfy it and thus pours out tears. (Dialogo)

‘A Companion to Catherine of Siena’ (Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition). The chapter written by Heather Webb titled: ‘Lacrime Cordiali: Catherine of Seina on the Value of Tears’