In spite of the laments of Durtal at having to leave Ligugé, those who were the intimate friends of Huysmans are clearly of opinion that he would not, in any case, have stayed there much longer. He had no real love of the country, he detested ‘the provinces’ in all that the word implies, he disliked the local inhabitants, he had even begun to fall out of love with the monks.

Gustave Coquiot¹ says that he felt around him an atmosphere of hostility it was impossible to mistake. It was inevitable that it should be so. The monks did not understand his extremely personal attitude to religion; they were shocked by his freedom of speech. From the literary point of view the law against the monasteries was a God-send to Huysmans. It enabled his experiment in oblature to end with a bang instead of a whimper. He came back to Paris, says Coquiot, exhausted and cast-down but yet with the firm, if unacknowledged, conviction that he really couldn’t live anywhere else.

Hearing of his return, François Coppée offered him an apartment in the house where he lived himself: No. 12 Rue Oudinot. It was a pleasant apartment with the use of a garden and at a reasonable price, and Huysmans was ready to move in. Unfortunately the proprietor, on hearing that a famous novelist was about to become his tenant, put up the rent.

We know that the Prior of Ligugé had proposed that he should take refuge with the Benedictine nuns in the Rue Monsieur, and this he now decided to do. He did not like the room that was offered to him, but Jean de Caldain, whom we have already seen performing kindly services for him, pointed out that he had only a few steps to go in order to reach the chapel; and there was room for his books. Huysmans was installed.

He tried count his blessings. The fact that the gate was shut at nine o’clock at night excused him from all invitations to dine out. In fact, from this point of view he was better off than he had been at Ligugé; the monastic atmosphere was more pronounced. All the passing Benedictines looked in (there were many of them in Paris owing to the upheaval) and one of these, Dom Dubourg, formerly Prior of the Paris Benedictine house of St. Marie, was actually lodged in the room above. He became Huysmans’ confessor and friend.

While still in his own monastery Dom Dubourg had heard of Huysmans’ conversion and had read En Route, as he confesses, with a mixture of admiration and repugnance. He was moved by its apparent sincerity and outraged by its realism, and for long he was unconvinced that the conversion was real. His doubts vanished when he met the author, although he was still puzzled by the contrast between Huysmans in private life, simple, natural and affable, and the creator of so many strange characters and shocking situations.

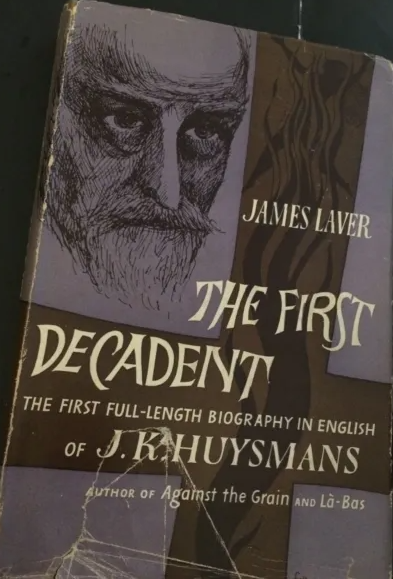

‘The First Decadent: Being the Strange Life of J.K. Huysmans’ written by James Laver