Chastity, according to St. Thomas Aquinas, is a quality of one’s being. It is an abiding orderliness among all of one’s sexual instincts, emotions, thoughts, and aims. As a result of having this abiding inner orderliness, one’s sexual impulses do not control the person but the person controls his or her sexual impulses with ease and joy. The chaste person is thus free to live out his or her sexuality in a way that leads to true happiness and avoids counterfeit happiness. Chastity comes from grace and the practice of self-control. Without it, people tend to fall into sexual sin and contract still further physical, psychological, and spiritual wounds. These wounds conspire to make self-control still harder. Chastity is often, therefore, something one arrives at over time. There is a road to chastity. It can be a hard road with many falls and frequent repentance. But it is a road that gradually frees the person from enslavement to sexual impulses and leads a man or woman to a happy self-mastery. –Angelic Warfare Confraternity website

Archives

J.K. Huysmans ventures into the mountains on a Marian pilgrimage

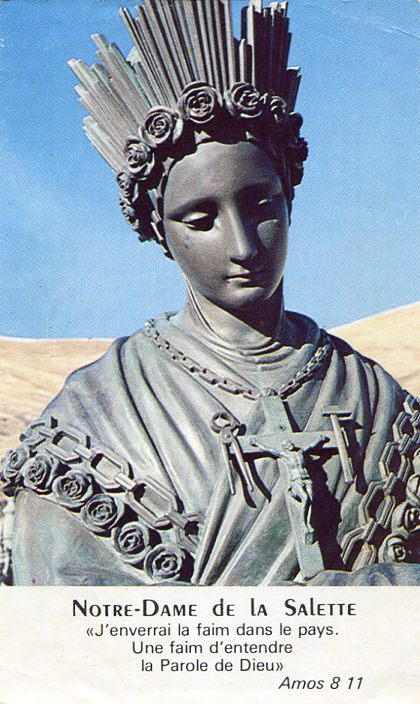

Huysmans continues the conversion of the French writer/aesthete Durtal in the novel ‘Cathedral’. The Cathedral referred to by the title is Chartres. Consecrated in 1260, in the presence of King St Louis, Chartres represents majestically to Durtal all that he pursues in his rejection of decadent modernism and the embracing of a profound Catholic medieval faith. A wearied cultured man, he reverses time in order to move forward spiritually. Appropriate with the anniversary of Fatima, Huysmans opens the second novel of the Durtal Trilogy with an examination of Our Lady’s apparition at the remote Alps town of La Salette, an apparition striking solely based upon foreshadowing similarities with Lourdes and Fatima. Huysmans writes in the most devoted manner of Our Lady. Keep in mind ‘Cathedral’ was written in 1898, before Fatima. Huysmans disturbing and grand descriptions of the geography surrounding La Salette proves spiritually revealing—a cryptic revelation.

He (Durtal) thought of the Virgin, whose watchful care had so often preserved him from unexpected risk, easy slips, or greater falls. Was not She the bottomless Well of goodness, the Bestower of the gifts of good Patience, the Opener of dry and obdurate hearts? Was She not, above all, the living and thrice Blessed Mother?

Bending forever over the squalid bed of the soul, she washes the sores, dresses the wounds, strengthening the fainting weakness of converts. Through all the ages She was the eternal supplicant, eternally entreated; at once merciful and thankful; merciful to the woes She alleviates, and thankful to them too. She was indeed our debtor for our sins, since, but for the wickedness of man, Jesus would never have been born under the corrupt semblance of our image, and She would not have been the immaculate Mother of God. Thus our woe was the first cause of Her joy; and this supremist good resulting from the very excess of Evil, this touching though superfluous bond, linking us to Her, was indeed the most bewildering of mysteries; for Her gratitude would seem unneeded, since Her inexhaustible mercy was enough to attach Her to us forever.

Thenceforth, in Her immense humility, She had at various times condescended to the masses; She had appeared in the most remote spots, sometimes seeming to rise from the earth, sometimes floating over the abyss, descending on solitary mountain peaks, bringing multitudes to Her feet, and working cures…

…On the 19th of September, 1846, the Virgin had appeared to two shepherd children on a hill; it was a Saturday, the day dedicated to Her, which, that year, was a fast day by reason of the Ember week. By another coincidence, this Saturday was the eve of the Festival of Our Lady of Seven Sorrows, and the first vespers were being chanted when Mary appeared as from a shell of glory just above the ground.

And she appeared as Our Lady of Tears in that desert landscape of stubborn rocks and dismal hills. Weeping bitterly, She had uttered reproofs and threats; and a spring, which never in the memory of man had flowed excepting at the melting of the snows, had never since been dried up.

The fame of this event spread far and wide; frantic thousands scrambled up fearful paths to a spot so high that trees could not grow there. Caravans of the sick and dying were conveyed, God knows how, across ravines to drink the water; and maimed limbs recovered, and tumors melted away to the chanting of canticles.

…there are no fir trees, no beeches, no pastures, no torrents; nothing—nothing but total solitude, and silence unbroken even by the cry of a bird, for at that height no bird is to be found.

“What a scene!” thought Durtal, calling up the memories of a journey (to La Salette) he had made with the Abbé Gévresin (spiritual director) and his housekeeper, since leaving La Trappe (‘En Route’ monastery). He remembered the horrors of a spot he had passed between Saint Georges de Commiers and La Mure, and his alarm in the carriage as the train slowly travelled across the abyss. Beneath was darkness increasing in spirals down to the vast deeps; above, as far as the eye could reach, piles of mountains invaded the sky.

The train toiled up, snorting and turning round and round like a top; then, going into a tunnel, was swallowed by the earth; it seemed to be pushing the light of day away in front, till it suddenly came out into a clearing full of sunshine; presently, as if it were retracing its road, it rushed into another burrow, and emerged with the strident yell of a steam whistle and deafening clatter of wheels, to fly up the winding ribbon of road cut in the living rock.

Suddenly the peaks parted, a wide opening brought the train out into broad daylight; the scene lay clear before them, terrible on all sides.

“Le Drac!” (the river) exclaimed the Abbé Gévresin, pointing to a sort of liquid serpent at the bottom of the precipice, writhing and tossing between rocks in the very jaws of the pit.

For now and again the reptile flung itself up on points of stone that rent it as it passed; the waters changed as though poisoned by these fangs; they lost their steely hue, and whitened with foam like a bran bath; then the Drac hurried on faster, faster, flinging itself into the shadowy gorge; lingered again on gravelly reaches, wallowing in the sun; presently it gathered up its scattered rivulets and went on its way…the rippling rings spread and vanished, skinned and leaving behind them on the banks a white granulated cuticle of pebbles, a hide of dry sand.

Durtal, as he leaned out of the carriage window, looked straight down into the gulf; on this narrow way with only one line of rails, the train on one side was close to the towering hewn rock, and on the other was the void. Great God! if it should run off the rails! “What a crash!” thought he.

And what was not less overwhelming than the appalling depth of the abyss was, as he looked up, the sight of the furious, frenzied assault of the peaks. Thus, in that carriage, he was literally between the earth and sky…along interminable balconies without parapets; and below, the cliffs dropped avalanche-like, fell straight, bare, without a patch of vegetation…all round lay a wide amphitheater of endless mountains, hiding the heavens, piled one above another, barring the way to the travelling clouds, stopping the onward march of the sky…

The landscape was ominous; the sight of it was strangely discomfiting; perhaps because it impugned the sense of the infinite that lurks within us. The firmament was no more than a detail, cast aside like needless rubbish on the desert peaks of the hills. The abyss was the all-important fact; it made the sky look small and trivial, substituting the magnificence of its depths for the grandeur of eternal space.

The Abbé had said that the Drac was one of the most formidable torrents in France; at the moment it was dormant, almost dry; but when the season of snows and storms comes it wakes up and flashes like a tide of silver, hisses and tosses, foams and leaps, and can in an instant swallow up villages and dams.

“It is hideous,” thought Durtal. “That bilious flood must carry fevers with it; it is accursed and rotten…Durtal now thought over all these details; as he closed his eyes he could see the Drac and La Salette.

Chartres

La Drac 1900

May the Lord give you His Peace

“In the solitude and silence of the wilderness, for their labour in the contest, God gives His athletes the reward they desire: a peace that the world does not know and joy in the Holy Spirit.” — St. Bruno von Köln, Founder of the Carthusian order.

End of the first book in a trilogy, the world awaits a life of faith

And in fact, Durtal had only time to shake hands with the father, who put his luggage into the carriage.

There, when he was alone, seated, looking at the monk as he departed, he felt his heart swell, ready to break.

And in the clatter of the rails the train started.

Sharply, clearly, in a minute, Durtal took stock of the frightful disorder into which he had thrown the monastery.

“Ah! and outside it, all is the same to me, and nothing matters to me,” he cried. And he groaned, knowing that he should never more succeed in interesting himself in all that makes the joy of men. The uselessness of caring about any other thing than Mysticism and the liturgy, of thinking about aught else save God, implanted itself in him so firmly that he asked himself what would become of him at Paris with such ideas.

He saw himself submitting to the confusion of controversies, the cowardice of conventionality, the vanity of declarations, the inanity of proofs. He saw himself bruised and thrust aside by the reflections of everybody, obliged henceforward to advance or retire, dispute or hold his tongue?

In any case peace was forever lost. How in fact was he to rally and recover when he was obliged to dwell in a place of passage, in a

soul open to all winds, visited by a crowd of public thoughts?

His contempt for relations, his disgust for acquaintances grew on him. “No, everything rather than mix myself again with society,” he declared to himself, and then he was silent in despair, for he was not ignorant that he could not, apart from the monastic zone, live in isolation. After a short time would come weariness and a void, therefore why had he reserved nothing for himself, why had he trusted all to the cloister? He had not even known how to arrange the pleasure of entering into himself, he had discovered how to lose the amusement of bric-à-brac, how to extirpate

that last satisfaction in the white nakedness of a cell! he no longer held to anything, but lay dismantled, saying, “I have renounced almost all the happiness which might fall to me, and what am I going to put in its place?”

And terrified, he perceived the disquiet of a conscience ready to torment itself, the permanent reproaches of an acquired luke-warmness, the apprehensions of doubts against Faith, fear of furious clamors of the senses stirred by chance meetings.

And he repeated to himself that the most difficult thing would not be to master the emotions of his flesh, but indeed to live Christianly, to confess, to communicate at Paris, in a church. He never could get so far as that, and he imagined discussions with the Abbé Gévresin, his gaining time, his refusal, foreseeing that their friendship would come to an end in these disputes.

Then where should he fly? At the very recollection of the Trappist monastery the theatrical representations of St. Sulpice made him jump. St. Severin seemed to him distracted and worn. How could he live among stupid people like the devout, how listen without gnashing his teeth to the affected chants of the choirs? How, lastly, could he seek again in the chapel of the Benedictine nuns, and even at Notre Dame des Victoires, that dull heat radiating from the souls of the monks, and thawing little by little the ice of his poor being?

And then it was not even that. What was truly crushing, truly dreadful, was to think that doubtless he would never again feel that admirable joy which lifts you from the ground, carries you, you know not where, nor how, above sense.

Ah, those paths at the monastery wandered in at daybreak, those paths where one day after a communion, God had dilated his soul in such a fashion that it seemed no longer his own, so much had Christ plunged him in the sea of His divine infinity, swallowed him in the heavenly

firmament of His person.

How renew that state of grace without communion and outside a cloister? “No; it is all over,” he concluded.

And he was seized with such an access of sadness, such an outburst of despair, that he thought of getting out at the first station, and returning to the monastery; and he had to shrug his shoulders, for his character was not patient enough nor his will firm enough, nor his body strong enough to support the terrible trials of a novitiate. Moreover, the prospect of having no cell to himself, of sleeping dressed higgledy-piggledy in a dormitory, alarmed him.

But what then? And sadly, he took stock of himself.

“Ah!” he thought, ” I have lived twenty years in ten days in that convent, and I leave it, my brain relaxed, my heart in rags; I am done for, forever. Paris and Notre Dame de l’ Atre have rejected me each in their turn like a waif, and here I am condemned to live apart, for I am still too much a man of letters to become a monk, and yet I am already too much a monk to remain among men of letters.”

He leapt up and was silent, dazzled by jets of electric light which flooded him as the train stopped.

He had returned to Paris.

“If they” he said, thinking of those writers whom it would no doubt be difficult not to see again, “if they knew how inferior they are to the lowest of the lay brothers! if they could imagine how the divine intoxication of a Trappist swine-herd interests me more than all their conversations and all their books! Ah! Lord, that I might live, live in the shadow of the prayers of humble Brother Simeon!” –J.K. Huysmans ‘En Route’

The Kingdom of Mediocrity

A deeper insight into souls gradually allows us to discover that behind possibly disappointing exteriors often lie real treasures of interior life, of generosity, and of an authentic search for God. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that these precious gems are often buried in unattractive dress. How could it be otherwise, face to face with the Absolute? Is this not the price of such dangerous proximity to fire? For it highlights all our faults, all our roughness of character and all the petty misery which in other circumstances would be swallowed up in the surrounding sea of trivialities. To wish to come face to face with the light of God is deliberately to consent to expose all our faults and pettiness to the hard light of day. These first become apparent to others, and then, as we become enlightened, to ourselves. We first discover mediocrity in others and afterwards, in ourselves.

Risks are always involved when our aim is high. Seeing our-selves apparently ever more distant and removed from our goal is a painful suffering. On a more prosaic level, this mediocrity is the consequence of our separation from the world. To the extent that solitude is effective, it deprives us of a great many advantages which might introduce into the community an élan or a renewal which would mask the mediocrity or remedy it in some way. The critical choice must be made: either choose God and accept that perfection must come first and foremost from within, or leave open certain gates to the world so that certain means, other than those proper to the desert, play a part in one’s life. The usual choice in the Charterhouse is the former. To make such a decision quite deliberately represents a very real sacrifice — an entry into solitude at a very exacting price. In effect, it is a conscious decision to leave untapped a part of our human potential so that God may well up from within. Such conditions are only suitable for those who have already attained a certain level of human maturity and self-motivation in their spiritual and intellectual life.

The discovery of mediocrity first in others and then in oneself is a step towards an even more disconcerting discovery. Holiness, perfection and virtue — all these qualities which, without realizing it, we believed to be reflections of the Absolute within ourselves — begin to vanish. Everything which tends to make the ego a point of reference or an autonomous centre must disappear in order to conform with the resurrected Christ who is but pure relation to the Father. Even his humanity is now endowed with divine names. All created riches have been stripped away in order to be nothing but pure relation.

Such is the direction which the monk must take little by little: first, in his interior life and then in all his activities, whether in cell or in community. He must learn never to focus on himself but to be taken up in the movement of a divine love which has neither beginning nor end, neither goal nor source, neither limit nor shape. He must surrender to the breath of the Spirit, without knowing whence he comes nor whither he goes. —Meditation on the Carthusian Vocation. Transfiguration Chartreux.

A Sacrament and feast day

“Today the Lord said to me, ‘Daughter, when you go to confession, to this fountain of My mercy, the Blood and Water which came forth from My Heart always flows down upon your soul and ennobles it. Every time you go to confession, immerse yourself entirely in My mercy, with great trust, so that I may pour the bounty of My grace upon your soul. When you approach the confessional, know this, that I Myself am waiting there for you. I am only hidden by the priest, but I Myself act in your soul. Here the misery of the soul meets the God of Mercy. Tell souls that from this fount of mercy souls draw graces solely with the vessel of trust. If their trust is great, there is no limit to My generosity. The torrent of grace inundate humble souls. The proud remain always in poverty and misery, because My grace turns away from them to humble souls.” –Diary of St Faustina

Leprous observing

…and recalled one evening, when he had wandered under a fine rain along the quays. He had been driven from home by ignoble visions, and at the same time had been harassed by the increasing disgust of his vices. He had ended by being brought up against his will at St. Gervais.

In the chapel of the Virgin, some poor women were prostrate. He had knelt, tired and dazed, his soul so ill at ease, that he slumbered without power to wake himself. Some men and boys of the choir were installed in the chapel, with two or three priests; they had lighted candles, and the voice, light and sustained, of a child, had in the dark of the church chanted the long antiphons of the “Rorate.”

In the state of overwhelming sadness in which he was stagnant, Durtal felt himself open and bleeding to the bottom of his soul; then a voice older and less trembling, which understood the words it said, narrated ingenuously, almost without confusion, to the Just One, “Peccavimus et facti sumus tanquam immundus nos”

And Durtal took up these words, and spelt them over in terror, thinking, “Ah! yes, we have sinned and become like the leprous, O Lord!” And the chant continued, and in His turn, the Most High borrowed that same innocent organ of childhood, to declare to man His pity, and to confirm to him the pardon assured by the coming of the Son. And the evening had ended by the Benediction in plain chant, in the midst of the silence and prostration of unhappy women.

Durtal remembered how he left the church refreshed, freed from his hauntings, and he had gone away in the drizzling rain, surprised that the way was so short, humming the “Rorate,” of which the air had taken possession of him, ending by seeing in it the personal touch of a kindly unknown. –J.K. Huysmans ‘En Route’

Drop down, ye heavens, from above,

and let the skies pour down righteousness

Be not wroth very sore, O Lord,

neither remember iniquity for ever:

thy holy city is a wilderness,

Sion is a wilderness, Jerusalem a desolation:

our holy and our beautiful house,

where our fathers praised thee.

We have sinned, and are as an unclean thing,

and we all do fade as a leaf:

and our iniquities, like the wind, have taken us away:

thou hast hid thy face from us:

and hast consumed us, because of our iniquities.

Behold, O Lord, the affliction of thy people,

and send forth him whom thou wilt send;

send forth the Lamb, the ruler of the earth,

from Petra of the desert to the mount of the daughter of Sion:

that he may take away the yoke of our captivity.

Ye are my witnesses, saith the Lord,

and my servant whom I have chosen;

that ye may know me and believe me:

I, even I, am the Lord, and beside me there is no Saviour:

and there is none that can deliver out of my hand.

Comfort ye, comfort ye my people;

my salvation shall not tarry:

why wilt thou waste away in sadness?

why hath sorrow seized thee?

Fear not, for I will save thee:

For I am the Lord thy God,

the Holy One of Israel, thy Redeemer.

Recent Comments