At the mountain of God, Horeb,

Elijah came to a cave where he took shelter.

Then the LORD said to him,

“Go outside and stand on the mountain before the LORD;

the LORD will be passing by.”

A strong and heavy wind was rending the mountains

and crushing rocks before the LORD—

but the LORD was not in the wind.

After the wind there was an earthquake—

but the LORD was not in the earthquake.

After the earthquake there was fire—

but the LORD was not in the fire.

After the fire there was a tiny whispering sound.

When he heard this,

Elijah hid his face in his cloak

and went and stood at the entrance of the cave.

1 Kings chapter 19

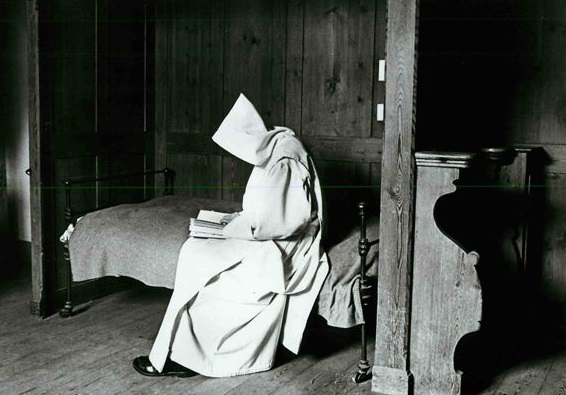

The preparation for listening to God is listening to others. The Statutes insist on the quality of welcome we are to offer to our brothers when we have occasion to converse with them or to relate to them; we must know how to listen to them, and understand them with both heart and mind; we are to go beyond mere appearance, and not allow ourselves to be troubled by the different ways they may have of approaching the same questions. So the Statutes give us a whole pedagogy of what it means to listen. Listening to others is not the aim of our life, to be sure, but welcoming our neighbor in this way will train our hearts to become silent, in order to be ready to receive the secret of the Other. For, in whatever circumstances, our main concern must not be just to receive some message or other, but, through the message, to discover the depth of the heart of the one who is speaking to us. If we are not able to do this with the brothers we can see, how will we be able to do it with God whom we cannot see?

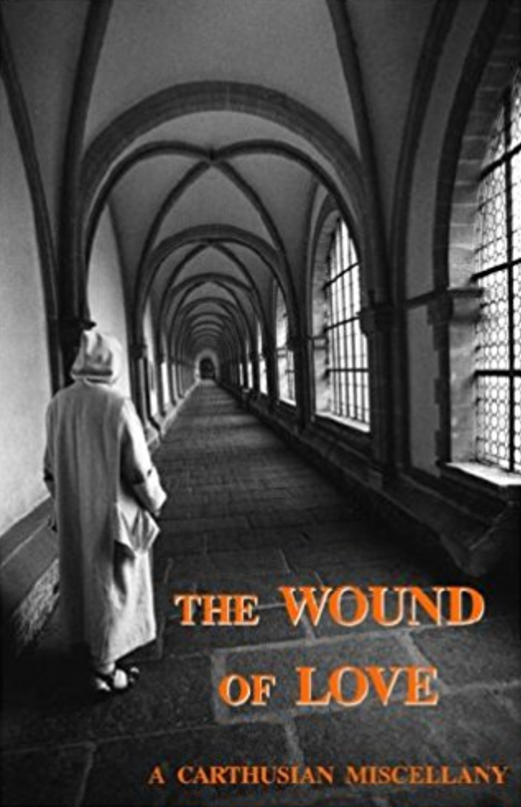

These are only brief indications, but enough for you to see how this touches on the very heart of our life of solitude. This solitude does not consist in shutting ourselves away between four walls in order to cut ourselves off; or refusing to welcome others; or trying to be alone with ourselves at all costs. On the contrary, solitude is the privileged place for listening, a place of silence; so, not a place of emptiness, but of communion with a reality which cannot be expressed in words. Normally, then, it is with joyous enthusiasm that we set off to master silence and the art of listening. However, experience shows that the results often fall short of our expectations. –‘The Wound of Love’ by A. Carthusian

Inspiration received—a book, and listened to, from the Cuban poet after Mass. Replace Rome with modern civilization.

Dear Sir,

I received your letter August 29th in Florence, and it has taken me this long—two months—to answer. Please forgive this tardiness, but I don’t like to write letters while I am traveling because for letter-writing I need more than the most necessary tools: some silence and solitude and a not too unfamiliar hour.

We arrived in Rome about six weeks ago, at a time when it was still empty, the hot, the notoriously feverish Rome, and the circumstance, along with other practical difficulties in finding a place to live, helped make the restlessness around us seem as if it would never end, and the unfamiliarity lay upon us with the weight of homelessness. In addition, Rome (if one has not yet become acquainted with it) makes one feel stifled with sadness for the first few days: through the gloomy and lifeless museum atmosphere that it exhales, through the abundance of its pasts, which are brought forth and laboriously held up (pasts on which a tiny present subsists), through the terrible overvaluing, sustained by scholars and philologists and imitated by the ordinary tourist in Italy, of all these disfigured and decaying Things, which, after all, are essentially nothing more than accidental remains from another time and from a life that is not and should not be ours. Finally, after weeks of daily resistance, one finds oneself somewhat composed again, even though still a bit confused, and one says to oneself: No, there is not more beauty here than in other places, and all these objects, which have been marveled at by generation after generation, mended and restored by the hands of workmen, mean nothing, are nothing, and have no heart and no value–but there is much beauty here, because everywhere there is much beauty. Water infinitely full of life move along the ancient aqueducts into the great city and dances in the many city squares over white basins of stone and spread out in large, spacious pools and murmurs by day and lifts up its murmuring to the night, which is vast here and starry and soft with winds. And there are gardens here, unforgettable boulevards, and staircases designed by Michelangelo, staircases constructed on the pattern of downward-gliding waters, and as they descend, widely giving birth to step out of step as if it were wave out of wave. Through such impressions one gathers oneself, wins oneself back from the exacting multiplicity, which speaks and chatters there (and how talkative it is!) and one slowly learns to recognize the very few Things in which something eternal endures that one can love and something solitary (endures) that one can gently take part in. –‘Letters to a Young Poet’ by Rainer Maria Rilke

Recent Comments