We read in the Chronicles of St Francis, that a secular asked a good religious, why St John Baptist, having been sanctified in his mother’s womb, should retire to the desert, and lead there such a penitential life as he did. The good religious answered him, by first asking this question: pray why do we throw salt upon meat that is fresh and good? To keep it the better, and to hinder it from corruption, replied the other. The very same answer I give you, says the religious, concerning the Baptist; he made use of penance as of salt, to preserve his sanctity from the least corruption of sin as holy Church sings of him, “that purity of his life might not be tarnished with the least breath.” Now, if in time of peace, and when we have no temptation to fight against, it is very useful to exercise our bodies by penance and mortification, with how much more reason ought we do so in time of war, when encompassed with enemies on all side? St Thomas, following Aristotle’s opinion, says that the word chastity is derived from “chastise,” inasmuch as by chastising the body we subdue the vice opposite to chastity; and also adds, that the vices of the flesh are like children, who must be whipped into their duty, since they cannot be led to it by reason. –St Alphonsus Rodriguez ‘The Practice of Christian and Religious Perfection’.

Chastise: 1. To discipline, especially by corporal punishment. 2. To criticize severely. 3. Archaic to restrain; chasten. 4. Archaic. To refine; purify.

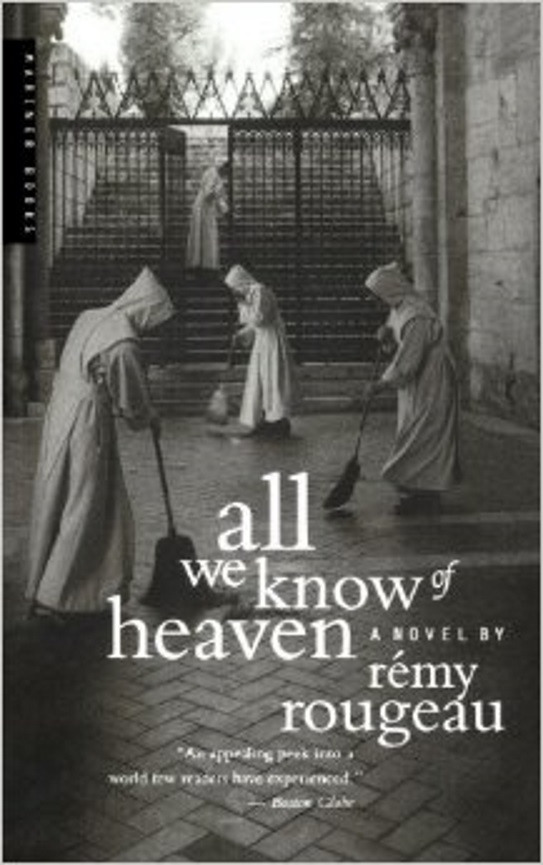

St Alphonsus Rodriguez writes guidance for the religious, yet I find his harsh, demanding perspective practical in contemplative pursuits as a layperson, while also touching upon a consideration into living a fully consecrated life. We are either fully in, or we are out. No dabbling. This is not a game of casualness, times of allowing explorations into the secular and nonreligious without salting ourselves. If we are not fully in, we must respect those fully in. Consideration and kindness are deeper than being casual and brash. Defenses must be up, ramparts in place, when journeying through life. I am reading a novel, ‘All We Know of Heaven” by Remy Rougeau, a Canadian Benedictine monk writing about a nineteen year old entering a Cistercian monastery. The novel captures me with its concise matter-of-fact, drab delivery; a boringness to the entire endeavor that pleases. Brutally honest realism, I suppose, with respect to Thomas Merton’s ‘Seven Story Mountain’. Poignantly ironic, I find the work of fiction realistic, and the biography delusional. In the novel there is not an underlying need for the author to establish himself as a recognized intellectual, an academic authority, a pop culture religious/literary celebrity. This is simply a monk telling a simple story. There is no great exploration of larger than life ideals, no religious history, nor romanticizing through flowery language, no desiring to expose the mystical and supernatural (a criticism I should consider reflectively), no tendency toward psychological self-absorbing introspections, no exposing of one’s inner-most being, no long sentences—saying so many things in a quick spewing. It is a simple realistic view into the occurrences within the life of a young man entering a Canadian Trappist monastery. Ordinary, yet set apart, an original thing in the world. Things can be defined by what they are not. “He walked into the house (his parent’s home after a week at the monastery) and felt as though he had returned from a foreign country; the television seemed a very odd contraption.”

No time, and thoughts are not coming out. I was aiming for the idea that God did not sacrifice His Son over two thousand years ago, and aside from the Church, basically disappear from the ways of man accidently. A God of order, there is a divine plan in place. It is difficult, demanding penance, mortification, and dedication, obviously trust and confidence, as well as obedience and surrender, the following of the ways of the Church if serious depth is to be achieved. Within and through the ordinary, the boring and mundane, we come into actualization, yet the process is difficult, the ways of the saints rigorous, brutal, and nearly impossible in regards to application. Divine assistance please subtly abide. The extraordinary existing within the ordinary takes a fine process of revealing; romantic traps, emotional enticements, egotistical needs, the desire for intellectual gratification, artistic expression, boredom, and the flesh are always posed for a gradual or immediate devouring. Not sure I am pleased with this entry, struggling personally with respect to perfection and longing for Ann–some days are difficult, yet never will I fully concede defeat, for as St Liguori teaches, the greatest defeat is to lose hope. My friend with the Catholic bookstore has a sign above her front door, above a holy water dispenser, ‘All yee who enter, abandon despair’. Always through faith, hope, charity and GRADUALNESS within fortitude, perseverance, and understanding–‘gratefulness for progress achieved’ maintained as a driving force, I move forward. To dabble or sit casually still is to die. The sitting still must be done with precise purpose, adorably and prayerfully in the presence of the Eucharist. Dentist appointment this morning, natural world calls, salting performed.