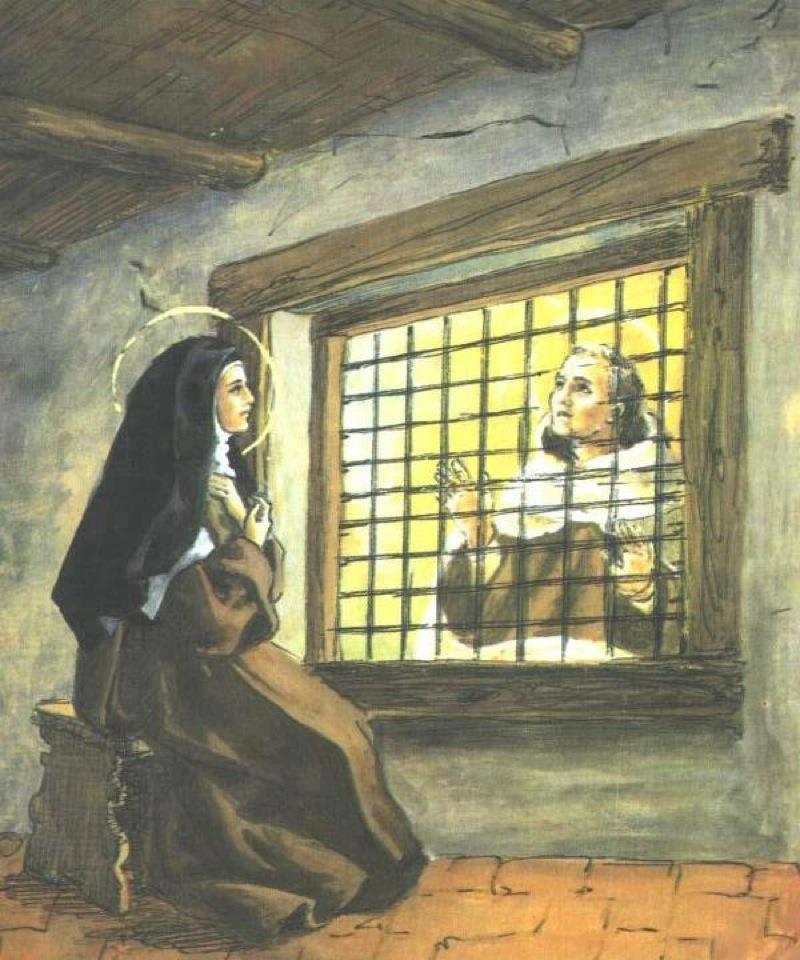

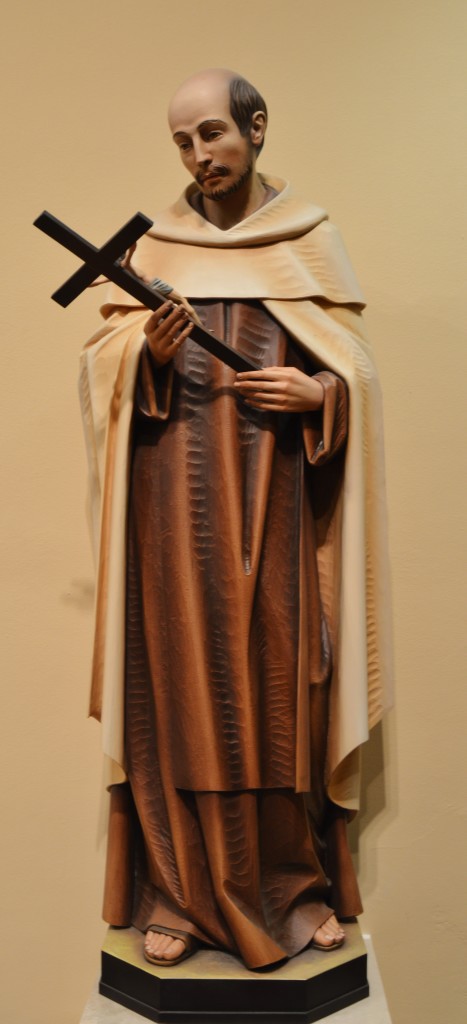

I was reflecting upon the insistence of St Teresa of Jesus that she was such a sinful person in her younger years. Was she really the vain girl and young nun she presents herself to be? As a child, she was never in severe trouble with her father, siblings, teachers, nor secular and religious authorities. She was loving and fully present for her parents, brothers, and sisters—all her family and friends. As a religious, she was obedient to her superiors, never in doubt, well liked and sociable to the point she was sent out to perform cheerful public relations, to raise funds and entertain benefactors. This persistence that she was such a vain and sinful (taken down by venial sins rather than mortal) individual needs to be closely examined. Her self-abnegation is a part of the process that allowed her to progress further into the sublime grace of unification, to enter the rarefied air of exemplary religious experience. It is easy for all of us to look around and observe the deeper vanity of those surrounding, yet to honestly and accurately penetrate ourselves with such scrutiny is another matter. To understand that all that I do is really about me is a truth that must be constantly embraced. I think of a recent listening to a modern-day Carmelite nun speaking on the saint, making the odd statement St Teresa might not be accepted into the order now based upon her acknowledgment that she entered out of a fear of God. The nun was trying to establish that fear was not a proper relationship with God. My critical, attacking, mind instantly snapped back: ‘no wonder your numbers are so low when you are so willing to reject a saint.’ Calming myself in reflection, I dissected why the nun irritated so intensely. In properly redefining God, as St Teresa puts it purifying our personal image (awareness) of God, it is important not to redefine, to break away from scripture and teachings of the Church. ‘Fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge.’ To reject the idea of fear being proper in our relationship with God is a grave error, a venal sin steering one away from the narrow path. In making peace with the nun, I understand what she is trying to accomplish, making everything warm and fuzzy—easily acceptable and non-abrasive, yet St Teresa penetrates deeper, willing to open herself fully to the mystery of God and the wisdom of the Church. We must not replace our known God based upon personal upbringing and understanding with further personal interpretation as we mature. Rather the unknown God of eternity working through the Church, the Trinity in reality, ascends, while descending, to a state of love, experience, and faith. To examine my own words, stripping away the vanity, yearnings, and insecurity contained within I can open myself greater to God. St Teresa was not exercising a false sense of humility, nor developing the negativity of scrupulosity. She was insightfully answering the questions: ‘who am I Lord?’ and ‘who are You?’ An overtly scrupulous person drives people away; the exercising of dogma, while inflicting the blessing of religion as a rigorous and punitive effort proves impossible in sustaining relationships. It is just another self-infliction of will upon the world, the imposing of law and the establishing of one’s self as an authority; being right becomes an obsession and an end itself. St Teresa was well loved, always drawing people to her, yet discerning in a deeper trust, recognizing those who it was proper to share her polished pearls with. She instantly recognized the youthful St John of the Cross as a giant in a diminutive body, establishing him as her first friar while he was just in his mid-twenties. She connected deeply with Saint Peter of Alcantara. Placed herself in obedience to Father Gracian while he was in his twenties and herslf in her sixties. She possessed the power of reading hearts and souls, while loving all—truly cherishing people, able to interact with a healthy temperament and cheerful disposition. She brought about a conservative reform with the care and compassion of a liberal. During the time of the brutal Spanish Inquisition, a time when those claiming supernatural experiences were closely scrutinized, enduring the trials of being reported to the Inquisition as a heretic and practicer of the supernatural by the Princess of Eboli, Anna de Mendoza, Saint Teresa’s humility and authenticity proved worthy of acceptance by all. She always knew how to get her way. Her greatest strength also being a weakness, a cause for self-criticism and her doggedness in declaring she was a vain creature. Just some early morning thoughts. Enough. I am committed to exercise this week as I finalize plans for a Carthusian retreat to Vermont next week. More will be expressed regarding the retreat. I am still working massive hours, finding it difficult to find the energy to write. My vacation request has not been approved yet.

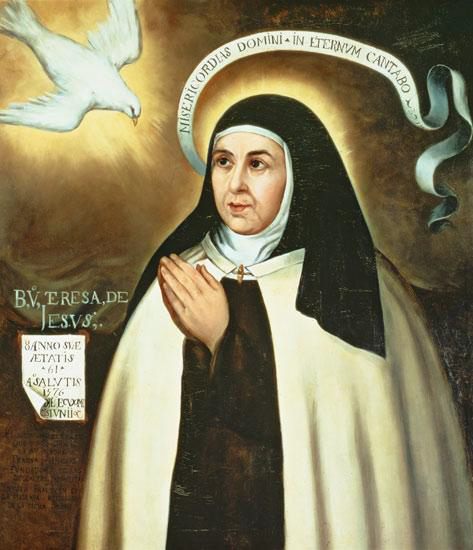

St Teresa of Jesus (Avila) on her youthful vanity

So, then, going on from pastime to pastime, from vanity to vanity, from one occasion of sin to another, I began to expose myself exceedingly to the very greatest dangers: my soul was so distracted by many vanities, that I was ashamed to draw near unto God in an act of such special friendship as that of prayer. As my sins multiplied, I began to lose the pleasure and comfort I had in virtuous things: and that loss contributed to the abandonment of prayer. I see now most clearly, O my Lord, that this comfort departed from me because I had departed from Thee. It was the most fearful delusion into which Satan could plunge me—to give up prayer under the pretense of humility. I began to be afraid of giving myself to prayer, because I saw myself so lost. I thought it would be better for me, seeing that in my wickedness I was one of the most wicked, to live like the multitude—to say the prayers which I was bound to say, and that vocally: not to practice mental prayer nor commune with God so much; for I deserved to be with the devils, and was deceiving those who were about me, because I made an outward show of goodness; and therefore the community in which I dwelt is not to be blamed; for with my cunning I so managed matters, that all had a good opinion of me; and yet I did not seek this deliberately by simulating devotion; for in all that relates to hypocrisy and ostentation—glory be to God!

I have asked others to recommend themselves to St. Joseph, and they too know this by experience; and there are many who are now of late devout to him, having had experience of this truth. I used to keep his feast with all the solemnity I could, but with more vanity than spirituality, seeking rather too much splendor and effect, and yet with good intentions. I had this evil in me, that if our Lord gave me grace to do any good, that good became full of imperfections and of many faults; but as for doing wrong, the indulgence of curiosity and vanity, I was very skillful and active therein. Our Lord forgive me! Would that I could persuade all men to be devout to this glorious Saint; for I know by long experience what blessings he can obtain for us from God. I have never known anyone who was really devout to him, and who honored him by particular services, who did not visibly grow more and more in virtue; for he helps in a special way those souls who commend themselves to him. It is now some years since I have always on his feast asked him for something, and I always have it. If the petition be in any way amiss, he directs it aright for my greater good.

Now and then, during the temptations I am speaking of, it seemed to me as if all my vanity and weakness in times past had become alive again within me; so I had reason enough to commit myself into the hands of God.

For though now—glory be to God!—I had no desire after vanities, I saw clearly in the vision how all things are vanity, and how hollow are all the dignities of earth; it was a great lesson, teaching me to raise up my desires to the Truth alone. It impresses on the soul a sense of the presence of God such as I cannot in any way describe, only it is very different from that which it is in our own power to acquire on earth. It fills the soul with profound astonishment at its own daring, and at any one else being able to dare to offend His most awful Majesty.

Recent Comments